Top videos

Prostitutes Charge Davos Attendees $2,500 a Night as Sex Work Demand Booms

Scores of sex workers have swarmed to the Swiss ski resort town of Davos to offer their services to the rich and powerful this week — with some said to be charging up to $2,500 a night.

Every year, the World Economic Forum hosts a five-day gathering featuring CEOs, dignitaries, captains of industry, and media figures to discuss important global issues.

One prostitute who goes by the name “Liana” told the German newspaper Bild that she frequently provides services to an American attendee at Davos who pays $750 per hour — or $2,500 to spend the whole night.

She added that she dresses in business attire in order to blend in with the crowd at the World Economic Forum gathering.

A woman who manages an escort service based in the Swiss town of Aargau, which is located some 100 miles from Davos, told 20 Minuten that she received 11 bookings and 25 inquiries — and that was just the beginning.

“Some also book escorts for themselves and their employees to party in the hotel suite,” the escort service manager said.

A German sex worker took to Twitter to describe her experience mingling with the Davos crowd and their security detail. Her comments were reported by DailyMail.com.

“Date in Switzerland during #WWF means looking at the gun muzzles of security guards in the hotel corridor at 2 a.m. – and then sharing the giveaway chocolates from the restaurant with them and gossiping about the rich… #Davos #WEF,” the sex worker, Salome Balthus, wrote.

Balthus, who said she is staying at a hotel near Davos, refused to divulge the names of her clients.

“Believe me, you don’t want to get into litigation with them,” she tweeted.

Balthus tweeted that politicians are unlikely to solicit the services of a prostitute.

“They have neither the time nor the desire,” she tweeted.

“You have to choose between a ‘drug’: sex or political power,” Balthus continued.

“The latter is stronger, it doesn’t leave room for other interests and eats up people completely.”

In 2020, a Swiss law enforcement official told The Times of London that at least 100 sex workers traveled to Davos in anticipation of the week-long event.

The prostitutes visit delegates’ hotels and bars along the town’s main strip, according to The Times.

At Luxury Property Care, we do more than just manage real estate. Luxury Property Care, is a joint endeavor founded by Sivan Gerges and Liran Koren that brings several different business entities owned by each into the ultimate property management concierge service. We are here to consolidate all the separate property care service that investors need into one all-inclusive package so we can deliver next-level profits and peace of mind to our clients. With all these resources under one roof, we offer unparalleled service at unbeatable prices to satisfy every property owner’s and investor’s wildest dreams..

For Quick Support:

Web: https://luxurypropertycare.com

Email: outreach@luxurypropertycare.com

Phone: (561) 944-2992

Address: 950 Peninsula Corp Circle, Boca Raton, Florida 33487, United States

Fraudci, the Mass Murdering Sociopath Gnome Says He Can’t Recall 174 Times at Convid Enquiry

An American Man On The Ground In Russia Says The Mainstream Media Reporting Of Protests Over Blaming Vladimir Putin For Alexei Navalny’s Death In A Russian Prison Is A Lie

He Says There’s No Protests, Just Members Of The Media

Most likely, it is about members of foreign media trying to create drama so that there is a reason to write.

Before that people left flowers and the police just secured the region

"90% of aid to Ukraine is actually spent in the US. This is beneficial for American industry"

This has never been about helping Ukraine

Trump warns that Biden is trying to go up against Russia which is a "war machine".

Trump & Putin 2024 = Peace

Farmers Know How to Deal With State Enforcers

BEFORE ELVIS BECAME THE "KING OF ROCK AND ROLL", IN THE EARLY 1950s,LITTLE RICHARD WAS COMPOSING, PLAYING AND RECORDING THE SONGS THAT MADE ELVIS PRESLEY FAMOUS. ONE OF THE FIRST ROCK AND ROLL HITS BY LITTLE RICHAQD WAS LUCILLE. THERE WERE TWO RECORDED VERSIONS: THE RADIO VERSION AND A SECOND ONE THAT HAD MORE HORNS SOUNDS. HERE ARE THE TWO IN ONE TRACK. ENJOY IT!

THIS IS THE SECOND IN A SHORT LITTLE RICHARD SERIES WITH SOME OF HIS EARLY HITS, SHOWING THAT HE WAS UNIQUE AND NO VERSION CAN COMPARE TO HIS ORIGINALS.

Mysterious green laser spotted in Texas during a “storm.”

Following this, over 1 MILLION acres have burned in Texas, the largest “wildfire” in US history.

BACK AT THE BIGINNING OF ROCK AND ROLL, BIG RECORD LABELS "STOLE" MUSIC FROM BLACK PERFORMERS AND RECORDED COVER VERSIONS BY WHITE ARTISTS AND SELLING LOTS OF RECORDS.

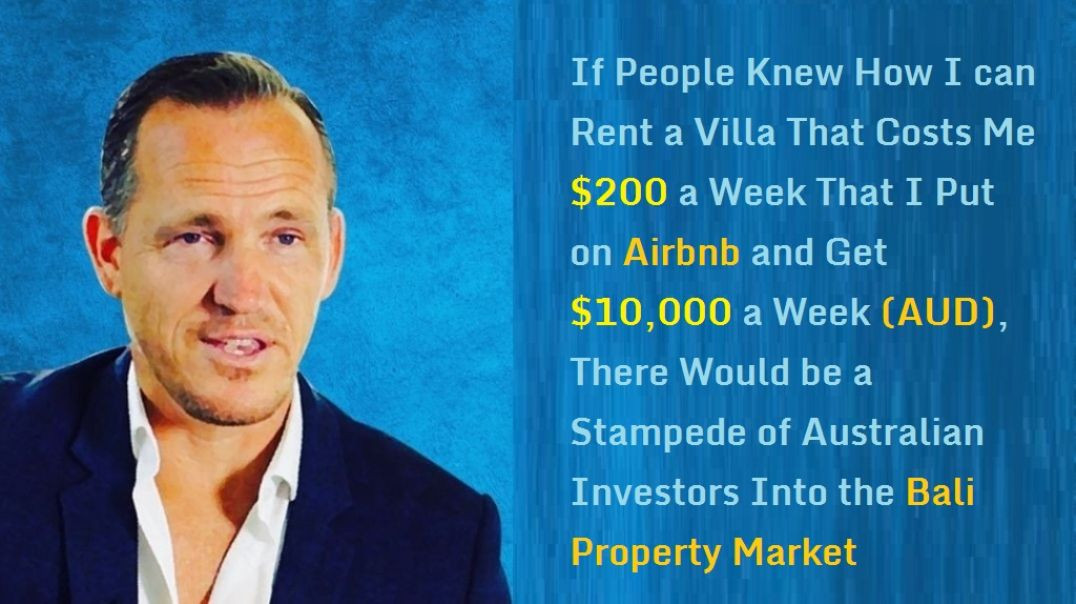

If People Knew How I can Rent a Villa That Costs Me $200 a Week That I Put on Airbnb and Get $10,000

If people knew how I can rent a villa that costs me $200 a week that I put on Airbnb and get $10,000 a week (AUD), there would be a stampede of Australian investors into the Bali Property market. So, best I don’t just let anyone know how it’s done safely and profitably! Or, maybe it’s best to stay heavily indebted to the Globalist bankers, buying Australian property and hoping not to be too old to still enjoy life by the time one’s bank debt is paid off. There must surely be a better way to live than as a Globalist bank’s debt slave…

https://property.21cuniversity.....com/optin1692252625

https://www.airbnb.com.au/rooms/851975490920612516?preview_for_ml=true&source_impression_id=p3_1680070582_%2BTF9onlIuN37O7hP&_set_bev_on_new_domain=1707207207_YjIyM2M0ZWNiNTFl

ANOTHER LITTLE RICHARD'S SONG "STOLEN" BY ELVIS AND BROUGHT BACK TO US FROM BRITAIN BY THE BEATLES IN 1964.

Turkish football weapon attack sparks chaos

A crazed fan stormed the pitch after the Fenerbahce squad beat his team Trabzonspor late on in their league match, and attempted to attack players with a knife.

The squad went scrambling for safety, fending for themselves in fighting off violent swathes of fans who then surged the pitch.

The incident follows a club president attacking the referee back in December which caused the league to be temporarily suspended.

FELICE PRIMAVERA 2024

Every single Senate Democrat voted against my amendment that would stop Biden Admin from using taxpayer dollars to charter flights for hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens from their countries directly to American towns to be resettled.

Indefensible.

In 2022, Candace Owens Spoke out Against an Elite Pedophile Ring in Hollywood and Highlighted that A

In 2022, Candace Owens spoke out against an elite pedophile ring in Hollywood and highlighted that anyone who speaks out against it gets fired.

She went on to expose Kim Kardashian for supporting Balenciaga after the fashion brand ran an advertisement in which they sexualized children.

IF YOU LIKE BLUES, HERE'S A SONG FOR YOU TODAY. ENJOY IT!

RFK. JR PRAISES ELON FOR RELEASING TWITTER FILES: “I WILL ALWAYS LOVE ELON”

"The Twitter files, which Elon Musk voluntarily released, an insane move.

All of his attorneys told him not to do it.

When he bought Twitter he found millions of documents that showed collusion between the White House and Twitter employees on censorship.

Instead of burning them, he invited the last living investigative journalists.

He gave them the documents and told them to do whatever they wanted with them.

I will always love Elon."

Source: The Rubin Report

German Police bashing women supporting Palestine in Berlin.

Could you imagine the outrage from the German Government if this was a video of the Russian Police in Moscow bashing women protesting?