Top videos

http://CompleteWealthEducation.com Jamie McIntyre discusses some simple yet very effective Stock Market Strategies such as Renting Shares at The 21st Century Academy. Please visit the link to get your FREE 3hr Wealth Creation DVD and 300 page E-Book right now.

Tecknat Barn Svenska:Tintin och de blå apelsinerna (1964) DVDRIPPEN (Franska) Hela Filmen (3D)

Tecknat Barn Svenska:Bröderna Daltons hämnd (1978) DVDRIPPEN (Svenska) Hela Filmen (HD)

The most important details in this text are the sentencing and aftermath of Leo Frank's trial. Judge Roan secretly brought Frank and the other principals together in the courtroom for the formal sentencing. The sentence read, "Leo M. Frank be taken from the bar of this court to the common jail of the county of Fulton and be safely there kept until his final execution in the manner fixed by law." On the 10th day of October 1913, the defendant was executed by the sheriff of Fulton County in private, witnessed only by the executing officer, a sufficient guard the relatives of such defendant and such clergyman and friends as he may desire, and that the defendant, between the hours of 10:00 A.m. and 02:00 p.m., be by the sheriff of Fulton County hanged by the neck until he shall be dead and may God have mercy on his soul." The trial had been the longest and most expensive trial in Georgia history, with the stenographic record being 1,080,060 words. The state star witness, Jim Conley, had been on the witness stand longer than any other witness in state history Judge Roan was Rosser's senior law partner from 1883 to 1886. The temper of the public mind was such that it invaded the courtroom and made itself manifest at every turn the jury made. This prejudice rendered any other verdict impossible. Frank's lawyers began to prepare their appeal immediately after the sentencing, including affidavits about the alleged prejudice towards Leo Frank of two members of the jury, A. H. Hensley and M. Johanning. The family of H. C. Lovenhard swore that on meeting Marcellus Johenning on the street before the trial he had told them, "I know he is guilty". Other points raised included the jurors being influenced by the crowd's demonstrations outside the courtroom and that the evidence did not support the verdict. Solicitor General Dorsey argued that the trial had been fair and countered with affidavits from eleven jurors who swore they did not hear or see demonstrations from crowds outside the courtroom. Both jurors who had been deemed prejudiced by the defense denied the charges. Rosser and Arnold made a final plea to Judge Roan, who denied the defense's motion for a new trial. The ruling was affirmed by the Georgia Supreme Court on February 17, 1914. Two judges, Beck and Fish, dissented on the question of admissibility of Jim Conley's testimony as to Frank's sexual perversion, but did not find the evidence in question sufficient cause to alter the guilty verdict. Not long after the Georgia Supreme Court decision, the Atlanta Journal reported that the state biologist who examined the body of Mary Phagan had concluded that the hair found on the lathe which the prosecution had cited as a major factor in its case, was not Mary Phagan's. The biologist told Solicitor General Dorsey that he did not depend on the biologist's testimony, as other witnesses in the case swore that the hair was that of Mary Phagan. The most important details in this text are that several prosecution witnesses retracted their original testimony, including Albert McKnight, Mrs. Nina Formby, George Epps, Jr., and Mary Phagan. Other witnesses conveyed that they had invented or lied about evidence due to the pressure brought by police detectives and solicitor Dorsey. In addition, the defense lawyers restudied the case, including Henry Alexander, who studied the murder notes allegedly written by Conley at Frank's direction, which were written on old carbon pads and had a dateline of September 19.

Mr. Alexander alleged that the words "night witch" in the note beside Mary Phagan's body, which had been interpreted to mean night watch or watchman by those who believed the notes had been written under the direction of a white man, actually referred to a negro folktale. On March 7, 1914, Frank was resentenced to die. A stay of execution was obtained on an extraordinary motion for a new trial based on newly found evidence. Three witnesses said the state's star witness, Jim Conley, was the killer. Annie Maud Carter in New Orleans said Conley told her he had called Mary Phagan over as she left Frank's office with her pay envelope, hit her over the head, and pushed her over a scuttle hole in the back of the building.

The most important details in this text are that Annie Maud Carter gave the Burns Agency some love letters from Conley which the Constitution said were so vile and vulgar that they couldn't be published in the newspaper. The defense contended that these love letters showed that Conley had perverted passion and lust. A black prisoner named Freeman told his story to the prison doctor, who reported that Conley was the killer. Conley's court appointed attorney, William Smith, thought Frank was innocent and made a public statement on October 2,114, saying that Conley's testimony was a cunning fabrication. This extraordinary revelation, which went against the lawyer client confidentiality privilege, was extolled by those who believed in Frank's innocence and castigated as being caused by bribery by those who believed him guilty.

William Smith revealed no new facts to support his beliefs, but instead tried to show how the already known facts had been misinterpreted due to Conley's lies. It has been said that Jim Conley confessed to William Smith, and a confession statement allegedly by Conley has been published in For One confessions of a Criminal Lawyer by Alan Lumpkin Henson. However, Walter Smith, William Smith's son, denied the authenticity of Conley's "confession", but brought to light facts which had been previously undisclosed regarding William Smith's relationship to his client. William Smith was reputed to be a very conscientious and ethical lawyer, and his prime obligation was to his client. He had been appointed to defend Conley by the court and he worked very closely with the prosecutor, Hugh Dorsey.

Smith believed in Frank's guilt and coached Jim Conley in how to react in the courtroom. He acted out the style and gyrations of Luther Rosser to Conley so well that when the actual trial was in session, Conley was not rattled in the least. Smith went to great lengths to defend Conley and to dig up facts against Frank. At some point in the course of the trial, Smith began to doubt that his client had been telling the truth and tried to get him the lightest sentence possible. Conley was convicted as an accessory to the fact and sentenced to one year on the chain gang. Smith felt morally and legally free to do some investigating and probing on his own.

William Smith believed that Leo Frank was innocent and that he himself was responsible for his conviction. He launched a thorough investigation which convinced him that Frank was innocent and that Conley was guilty. He went to Governor Slayton with his conclusions and his story was important in helping Slayton reach the decision to commute Frank's sentence. Smith's life was threatened and he and his family were forced to leave Georgia. In the last years of his life, Smith's vocal cords were paralyzed and he carried a pad of paper on which to write messages in the hospital room.

On May 8, 1914, superior court Judge Ben H.Hill denied the defense motion for a new trial, which was affirmed unanimously by the Georgia Supreme Court. Jewish organizations and groups raised the issue of religious prejudice before Leo Frank's trial ended. The appeals for funds for Leo Frank's defense were made through mailing, circulars and newspaper advertisements throughout the country and particularly in the north. This resulted in a virtual reenactment of the Civil War between Northern and southern newspapers, which increased in intensity as the trial progressed. The New York Times and Colliers Weekly called for a new trial, mass rallies were held in United States cities, and thousands of letters, petitions and telegrams were sent to Governor Slayton and soon to be Governor Nat Harris.

However, the conviction of Frank became an article of faith for Southerners and the belief in Frank's innocence became the litmus test in the Jewish community of Atlanta for antisemitism. On March 10, 1914, the Atlanta Journal editorially called for a new trial, saying that if Frank is found guilty after a fair trial, he should be hanged and his death without a fair trial and legal conviction will amount to judicial murder. The most important details in this text are that the court, lawyers, and jury were not able to decide impartially and without fear the guilt or innocence of an accused man. The atmosphere of the courtroom was charged with an electric current of indignation, and the streets were filled with an angry, determined crowd ready to seize the defendant if the jury had found him not guilty. When the jury returned the guilty verdict, Frank was not in the courtroom, but at the Fulton Tower.

Cheers for the prosecuting counsel were irrepressible in the courtroom throughout the trial, and on the streets, unseemly demonstrations and condemnation of Frank were heard by the judge and jury. The judge was powerless to prevent these outbursts in the courtroom and the police were unable to control the crowd outside. The Fifth Regiment of the National Guard was kept under arms throughout the night, ready to rush on a moment's warning to the protection of the defendant. The press of the city united in an earnest request to the presiding judge to not permit the verdict of the jury to be received on Saturday, as it was known that a verdict of acquittal would cause a riot. Frank was tried and convicted, but the evidence on which he was convicted is not clear.

The outbursts in the courtroom and the police were unable to control the crowds outside were events that all three newspapers had not printed during the trial. The Journal remained quiet about these events for a year.

The Atlanta Georgian, which was silent during the trial, later called for a new trial. Tom Watson, who had been defeated for vice president of the United States on the populace ticket in 1896, immediately launched a scathing attack against those criticizing the results of the Frank case. He referred to Frank as being a Jew pervert and said he denied justice to the family of a poor factory girl. Burns offered a $1000 reward to anyone who could provide evidence that Frank was a sexual pervert, but no one came forward. Burns also brought forth evidence given to him by the reverend C.B.Ragsdale, pastor of the Atlanta Baptist Church, who told the story of overhearing two black men, one of whom confessed to killing a little girl at the factory the other day. Later, Ragsdale repudiated his statement. A Burns operative, Mr. Toby, had been retained by members of the Phagan family and their neighbors to investigate the murder and discover the murderer. After several weeks of investigating, Toby resigned and announced that he had concluded that Frank was the guilty party. Dorsey alleged that Burns tried to bribe witnesses to give false testimony.

The hearing on extraordinary motion for a new trial was based on the absence of Frank at the reception of the verdict. On December 7, 1914, a writ of error was taken to the United States Supreme Court and was denied. Frank was sentenced to be hanged on January 22, 1915. Frank's attorneys then filed an application for a writ of habeas corpus to the United States Supreme Court on April 19, 1915. The two justices who dissented were Oliver Wendell Holmes and Charles Evans Hughes.

They dissented on the basis that a lower court hearing should have been held to determine the validity of the defense. The most important details in this text are that Governor John Slayton was the only hope left for Frank, and his attorneys appealed to him for a commutation of his sentence from hanging to life imprisonment. Slayton referred this request to the state Prison Commission and asked them to pass their recommendation to the governor. Meanwhile, Frank's attorneys filed an appeal for a clemency hearing before the three man Georgia Prison Commission. The hearing date was scheduled for May 31, 1915.

On May 31, 1915, out of state and in state delegations appeared to plead for Frank's life. They had submitted voluminous documents to convince the commission an error had been made, including a letter by presiding Judge Leonard Roan written shortly before his death on March 23, 1915. Some members of Roan's family doubted the authenticity of the letter for years, but Dr. Wallace E. Brown, owner of the Berkshire Hills Sanatorium, attested to Roan's rational mental state. Brown also stated that he has been a resident of North Adams, Massachusetts, practically all his life, and is now serving his third term as mayor of the city of North Adams.

On Sunday, November 20, 1914, Judge L.S. Roan of Atlanta, Georgia dictated a letter to Mrs. Wallace E.Brown of North Adams, Massachusetts, asking for executive clemency in the punishment of Leo M. Frank. The letter was written by Judge Roan of Atlanta, Georgia, to Mrs. Wallace E.Brown, who was then Miss Jane Deity. The letter expressed the deponent's uncertainty of Frank's guilt due to the character of the Negro Conley's testimony. The letter also stated that the chief magistrate of the state should exert every effort in ascertaining the truth, and that the execution of any person whose guilt has not been satisfactorily proven to the constituted authorities is too horrible to contemplate. The deponent heard Judge Roan dictate the letter before copied and saw him read and sign the name.

Judge Roan had stated to Deponent that he was not convinced of Frank's guilt and that if executive clemency were asked for Frank, he intended to recommend commutation. The next morning, some 50 determined looking men from Cobb County marched into the Prison Commission office and demanded the hearing be reopened. They included former governor Joseph M. Brown and Herbert Clay, solicitor of the Blue Ridge Circuit. Clay spoke for hours against Commutation arguing that Georgia would be dishonored for all time if Frank were spared for his alleged abominable crime. The commission reopened the hearing and the commissioners listened intently and said nothing.

At the end of the reopening, they issued a statement that they would offer their recommendation to Governor Slayton in a week by a two to one vote. On June 1915, the commissioners refused to recommend commutation to Governor Slayton, leaving it up to the governor.

Leo Frank was convicted on Monday, August 25, 1913, following the jury instructions provided by Judge Leonard Roan. Leo M. Frank was accused of choking Mary Phagan with a cord that was wrapped around her neck in an unlawful manner and with premeditation to kill and murder her. The jury was sworn to hear the case after the defendant entered a not guilty plea to the charge. The State had to prove its case by providing the jury with proof that proved the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt because the presumption of innocence was in the defendant's favor. Although beyond a reasonable doubt, the jury was not required to find him guilty.

Murder is defined as the unlawful killing of a human being in the peace of the State by a person of sound mind and discretion with malice of forethought, either express or implied. Express malice is the willful intent to unlawfully take another person's life that is demonstrated by external circumstances that can be used as evidence. When there is little to no indication of provocation and the entire situation surrounding the murder suggests a heartless, malicious intent, malice is presumed. Malice in a legal sense refers to a general evil plan rather than specific animosity toward the deceased. If a homicide is established to have been committed by the defendant, the law presumes that the defendant acted with malice, and the slayer may be found guilty of murder absent compelling evidence to the contrary.

Proof that the defendant committed the murder eliminates the presumption of innocence. It is the defendant's responsibility to defend the homicide after it is established that the defendant committed the murder. The rules of evidence, which are intended to discover the truth, are the most crucial details in this text. Direct evidence that directly refers to the subject at hand is the best type of evidence. Indirect or circumstantial evidence is that which only tends to establish the matter by proving various facts supporting by their consistency the hypothesis claimed to warrant a conviction on the basis of circumstantial evidence.

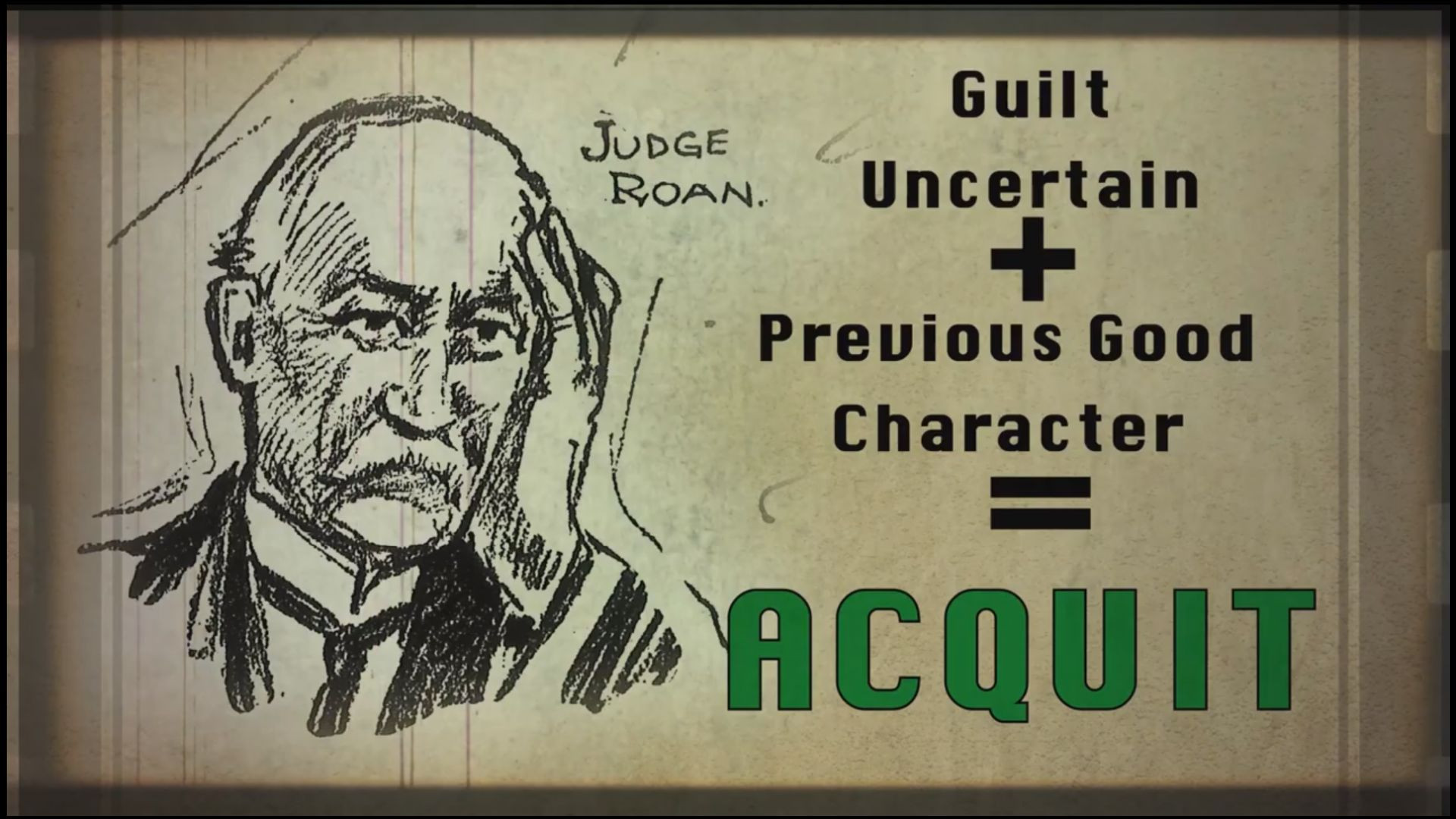

In addition to excluding all other reasonable doubt hypotheses other than the accused's guilt, the proven facts must be both consistent with and exclude the hypothesis of guilt. In a criminal case, the defendant has presented testimony attesting to his moral character, which the jury should take into account as one of the case's facts. Like any other substantial fact tending to establish the defendant's innocence, good character should be weighed and estimated by the jury. However, the jury must convict if the accused's guilt is established beyond a reasonable doubt and to their satisfaction.

The most crucial information in this passage is that the jury may take into account the defendant's good character if the rest of the testimony raises reasonable doubts about whether or not the defendant is guilty.

If the jury's perception of the defendant's guilt is reasonably raised by the consideration of the evidence and the defendant's good character, then the jury has a duty to grant the defendant the benefit of the doubt created by this and to find the defendant not guilty. When the term "character" is used in this context, it refers to the overall impression that person made on those who knew him before Mary Phagan passed away. When a defendant calls into question his character, the State is free to refute it by demonstrating that his reputation in general is not good or by demonstrating that the witnesses who have claimed that his character is good have misrepresented it.

The defense witnesses for the defense who were introduced to attest to his good character have the right to cross examine, and the Solicitor General has the right to pose any questions in this vein. The jury is not to consider this as evidence that the defendant has been guilty of any such misconduct unless the alleged witnesses testify to it, which is one of the most crucial details in this text. The Solicitor General was permitted to question the defendant's character witnesses about their knowledge of various acts of alleged misconduct on the part of the defendant.

Furthermore, when the defendant has called into question his character, the State is free to call witnesses to refute those who claim his character is strong by showing that it is weak overall. This testimony may be used by the jury, and they have the right to do so along with any other evidence that has been presented regarding the defendant's general character. To be found guilty of the crime for which they are accused, a defendant must, however, be proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt based on all other evidence in the case. The most crucial information in this text is that the jury can acquit the defendant if they think that the defendant's overall character was strong before Mary Phagan's death. However, if the jury finds the defendant guilty of murder beyond a reasonable doubt, they have the option of convicting him and punishing him with the death penalty by hanging him from a tree until he dies.

The defendant would have to accept the most severe punishment for murder, which is to be hanged by the neck until he dies, if the jury decides not to proceed with the case. The jury has been instructed by Judge Roan that the court must sentence the defendant to life in prison if the jury finds him guilty and recommends that he be held in a penal institution. The defendant's statement, which is not made under oath and is not open to questioning or cross-examination, has been heard by the jury. If the evidence raises a reasonable doubt in the jury's minds, they may acquit the defendant and state in their verdict: "We, the jury, find the defendant not guilty.". Judge Roan concluded his charge to the jury by stating that if the jury found the defendant not guilty, the court would have to sentence him to life in prison.

The jury began deliberation at 01:30 p.m. and at 04:39 p.m., they came to a unanimous decision. After a second and final vote, the verdict was guilty as charged and sentencing recommendation was without mercy, implying a death sentence for Leo Frank. The verdict was delivered to Judge Leonard A. Strickland Roan at 04:56 p.m. and each jury member was polled individually.

After Leo Frank gave an untruthful statement to the court, the defense called several women who claimed that they had never received any inappropriate sexual advances from Frank. A number of strong female witnesses from the prosecution's side, however, contradicted that testimony. These opposing witnesses also disputed Frank's assertions that he was so unfamiliar with Mary Phagan that he did not even recognize her name. Leo Frank's friends, business partners, and employees testified on his behalf in the defense, stating that he had a good reputation and had not, to their knowledge, made inappropriate sexual advances toward the girls and women who worked for him.

Mrs. Annie Osborne, Mrs. Rebecca Carson, Mrs. Maud Wright, and Mrs. Ella Thomas all testified that they worked for the National Pencil Company and that Mr. Frank generally had a good character while Conley generally lacked truthfulness and veracity. Cora Cowan, Mrs. Molly Blair, and Ethel Stewart. All of the defendant's witnesses—B.D. Smith, Lizzie Word, Bessie White, Grace Atherton, and Mrs. Barnes—proved that they worked for the National Pencil Company, knew Leo M. Frank, and thought well of him in general.

Miss Corinthia Hall, Annie Howell, Lillie M. Goodman, Velma Hayes, Jennie Mayfield, Ida Holmes, Willie Hatchett, Mary Hatchett, Minnie Smith, Marjorie McCord, Lena McMurty, Mrs. R. Johnson, Mrs. S. A. O. Wilson, Mrs. Georgia Denham, Mrs. O. Jones, Miss Zilla Spivey, Charles Lee, N.V. Darley, F. Ziganki together with A.C. Holloway and Minnie Foster all claimed that Leo M. Frank was a person of good character, who were all sworn witnesses for the defendant and who all worked for the National Pencil Company. Leo Frank never made any sexual advances toward any of the current National Pencil Company employees, according to numerous witnesses.

The other signatories were D.I. MacIntyre, Alex Dittler, Dr. B. Wildauer, Mrs. Dan Klein, and Ms. E. Sommerfield, F.G. Schiff, Joseph Gershon AL. Guthman; P.D. McCarley, Ms. M.W. Meyer, Mrs. David Marx, Mrs. I. Harris, M.S. Rice, L.H. Moss, Mrs. L.H. Joseph Brown, E. Moss, Mrs. E. Fitzpatrick, Emil Dittler, and W.M. Bauer, Miss Hellen Loeb, A.L. Fox, Mrs. Martin May, Julian V. Boehm, Mrs. Mollie Rosenberg, M.H. Silvermans, Mrs. L. Sterne, Chas Adeler, Mrs. Ray Klein, Miss R.A. Sonn, A.J. Jones, L. Einstein, J. Bernald, J. Fox, Marcus Loeb, Fred Heilbron, Milton Klein, Jonathan Coplan, and Mrs. J.E. Sommerfield. Leo M. Frank has lived in Atlanta all of his life, and according to Sommerfield, who were all sworn witnesses for the defendant, they have known him since that time. They also attested to his generally good character and that Leo Frank never made any sexual advances toward any of the current National Pencil Company employees, according to many of them who testified.

Mrs. M.W. Carson, Mary Pirk, Mrs. Dora Small, Miss Julia Fuss all testified positively on behalf of Leo Frank, He is a good person in general, according to R.P. Butler and Joe Stelker, both of whom were sworn witnesses for the defendant and who all stated that they worked for the National Pencil Company.

In their testimony, they further stated that they had never accompanied him for any immoral activities and that they had never heard of him breaking any laws. Maggie Griffin, Mrs. C. Duncan, and Mrs. Myrtie Cato were among the witnesses called by the prosecution. Mrs. Mary Davis, Miss Nelly Pettis, R. Johnson, Miss Marie Carst, Mrs. R. Mary, Mrs. E. Carrie Smith, Mrs. Estelle Winkle, and Mrs. Wallace. All of these witnesses confirmed that they worked for the National Pencil Company, knew Leo M. Frank, and thought well of him in general. The ten women who testified that Leo M. Frank had a "bad character for lasciviousness" were not chosen by the defense to be subjected to cross examination.

This limited the prosecution to the straightforward claims that Frank had a "bad character for lasciviousness.". At the coroner's inquest, where the rules of evidence allow for more lenient questioning, two of these witnesses gave much longer statements. During the inquest, several young women and girls testified that Frank had made inappropriate advances toward them, including touching a girl's breast and paying her to comply with his wishes.

According to The Atlanta Georgian, women and girls were called to the witness stand to confirm that Leo Frank had made an effort to get to know them and that they had either worked at or had occasion to visit the pencil factory. According to Nellie Pettis of Nine Oliver Street, Frank had made inappropriate advances toward her. When asked if she had ever worked at the pencil factory, she replied that she had seen him in his office occasionally while visiting the facility to collect her sister-in-law's paycheck. Frank looked at her after taking a box full of cash from his desk and giving it to her when she asked for her sister's pay. She immediately assured him that she was a nice girl. She told him to go to hell and walked out of Coroner Donohue's office after he sharply inquired, "Didn't she say anything else?". If accurate, Frank's actions in this regard were shocking.

The two young girls' testimony, which describes Leo Frank's pattern of improper familiarities, contains the most crucial information in this text. Frank asked Nellie Wood, a young girl who worked for him for two days, to come into his office so he could put his hands on her breast, according to testimony she provided. Frank's pattern of inappropriate familiarities was also attested to by Miss Ruth Robinson, Ms. Ruth Robinson, Ms. Jones, and Ms. Miss Ruth Robinson testified that she had seen Frank discussing Mary Phagan's work with her and that she had never met him for any immoral purposes. Miss Mamie Kitchens testified that she had never met Mr. Frank for any immoral purposes, regardless of where or when they had met.

Miss Ruth Robinson testified that she had seen Frank discussing Mary Phagan's work with her and that she had never met him for any immoral purposes. The most crucial information in this passage is about Miss Dewey. In rebuttal, Hewell swore on behalf of the state and stated that she had spent four months working at the pencil factory before leaving in March 1913. She had observed Mr. Frank speaking to Mary Phagan in the metal department two or three times per day while placing his hand on her shoulder. Both Ms. Myrtice Cato and Miss Maggie Griffin, who had taken the oath on behalf of the state, testified that they had seen Miss Rebecca Carson enter the woman's dressing room on the fourth floor while Leo M. Frank was present two or three times while the two were at work.

J.E. Duffy admitted to working for the National Pencil Company and swearing for the state in rebuttal. In March of this year, the narrator suffered an injury while working in the National Pencil Company's metal department. Their left hand's forefingers were cut, so they went to the office to get it dressed. When they were initially cut, a large piece of cotton was wrapped around their finger, and a piece of cotton waste was slapped onto their hand.

Cross-examination showed that there was no blood anywhere besides at the machine. They went to the hospital in Atlanta to have their finger treated, and Willie Turner gave a rebuttal oath on behalf of the state. Mary Phagan informed Leo Frank that she had to leave for work when the narrator overheard them discussing March middle on the second floor. The most crucial information in this passage is when Mr. Frank informed Mary Phagan that he was the factory superintendent and that he wanted to speak with her; however, she responded that she had to go to work. While this was going on, some of the girls entered the room as they were getting ready for dinner and directed the narrator to where to put the pencils. She informed Mr. Frank that she had to leave for work because of the whistle at noon when he said he wanted to speak to her. The narrator didn't know anyone in the factory, according to a young man on the fourth floor who introduced himself as Mary Phagan.

Leo Frank's defense made an impression with their parade of young female pencil factory workers who had never heard Frank speak to Mary Phagan. Finding someone who had seen Leo Frank make dubious forays into the lady's dressing room, who had been sexually approached by Frank or had seen him approach others, and who had seen Frank speak to Mary Phagan, however, was enough to shatter the façade of a Leo Frank who didn't know Mary Phagan and whose behavior toward his female employees was above reproach.

The damage it caused to Leo Frank's credibility as a truthful person was the most detrimental of all. George Gordon, Minola McKnight's attorney, testified about the events of the night that Minola McKnight wrote her sensational affidavit asserting that Leo Frank had admitted to his wife that he wanted to die because he had killed a girl that day after a motorman named Merck claimed that defense witness Daisy Hopkins had a reputation for lying. Minola McKnight, a cook for the Franks, had since George Gordon, a practicing attorney, was present at the police station for a portion of the time Minola McKnight was giving her statement.

He spent the majority of the time waiting for her to sign the affidavit outside the door. When he saw the sonographer from the recorder's court enter the room, he demanded to be allowed to do so and was granted his request. While he was gone, Mr. Starnes said it had to be kept quiet and nobody told about it. He found Mr. February reading over to her a stenographic statement he had taken. Gordon subsequently requested that Mr. Dorsey release her at his office. Gordon went to Mr. Dorsey's office and informed him that she was being held against her will even though he had said he would let her go. He told Gordon he had done it. The most significant information in this passage is that the narrator received bond in any amount she requested and that the narrator agreed with her that they had no right to imprison her. Once he had a habeas corpus, the narrator went to the police station to have her released. The detectives told them they would not release her unless the narrator demanded that they do, and the narrator agreed that they had no right to imprison her. In order to get her released, the narrator then obtained a habeas corpus and went to the police station.

The narrator heard that a woman had been detained and was being held in a cell at the police station. These are the two most crucial facts in this text. Beaver stated that since the charge against her was mere suspicion, he would not release her on bond without Mr. Dorsey's approval. When the narrator asked Mr. Dorsey to release her on bond, he responded that he wouldn't because it would make him look bad in the eyes of the detectives. However, if the narrator allowed her to stay with Starnes and Campbell for a day, he would release her without any bond. According to the narrator, while it is occasionally necessary to obtain information, our liberty is more important than any information, and we consider it to be a violation of our Anglo-Saxon liberties when someone is locked up simply because they know something.

The most crucial information in this passage is that Minola's lawyer, Mr. Dorsey, was present when she spoke about paying the cook, and that her husband, Albert McKnight, testified that the household's diagram was incorrect and did not depict the furniture in its proper locations. On April 26, the employers of Albert McKnight provided additional insight into Minola's statement because they had been present while she was being detained and even managed to coax her into speaking with them without the detectives being present.

These assertions supported Minola's affidavit and did not support her later denial of it. In rebuttal, R.L. Craven took the oath of the state. Albert McKnight also works for the same company as the hardware store where he had ties, Beck and Greg. In the latter part of May, he went to Minola McKnight's house with Mr. Pickett, and he was there when she signed the affidavit. She was first questioned about the statements Albert had made to them. She initially refused to speak, but eventually she spoke about everything that was stated in the affidavit. When they were questioning her, Mr. Starnes, Mr. Campbell, Mr. February, Mr. Pickett, Mr. Gordon, and Mr. Albert McKnight were present.

At the time of the 11:30 a.m. cross examination, she had been detained for 12 hours. One morning, the narrator went to Mr. Dorsey's office to see if they could help her get out of jail. She initially refuted it, but the narrator interrogated her for two hours. After a while of wondering why they didn't stay and free her, she finally said something in agreement with her husband, and the narrator left. Mr. Starnes and Mr. Campbell would be informed, according to Mr. Dorsey, who instructed the narrator to question her and go out and see her.

After some time wondering why they didn't stay and free her, the narrator left. The key information in this passage is that E.H. Minola McKnight, Albert McKnight, Starnes Campbell, Mr. Craven, and Mr. Gordon signed a document while Mr. Gordon and Beck and Greg employee Pickett was present. She initially denied everything when they questioned her about Albert's statement. She claimed that Albert had lied when he told Mrs. Frank and Mrs. Selig that she had been warned not to discuss the affair.

After a while, she started to back down from a few of her arguments and acknowledged that she had received a little more pay than was normally expected of her. Although initially she didn't tell us everything in that statement, there were many things she did not disclose. She appeared hysterical before starting to do it. We assured her that we had not come down to cause trouble for her but rather to rescue her. She consented to speak with us but refused to speak with the detectives. Following that, the detectives left the room.

The most crucial information in this passage is that Minola McKnight was detained and accused of a crime. The detectives bombarded her with questions while admonishing her not to repeat anything she heard.

The affidavit contains nothing that she did not say during her initial conversation with them; she did not make all of those claims. She was initially told not to speak, and the Seligs had increased her pay as a result of whatever, if anything, she may have said about being given a hat by Mrs. Selig. With the detectives being cross-examined as to why they declined to take her statement, her attorney, Mr. Gordon, entered the room.

Mr. Dorsey referred them to the detectives to make arrangements as to why they didn't get her out then when she denied saying all of those things. The testimony of Dr. S.C. Benedict and a couple of streetcar motormen, such as J.H. Hendricks and J.C. McEwing - both being motormen for Georgia Railway and Electric Company contains the majority of the crucial information in this recording. Dr S.C. Benedict stated that Dr. Harris, the prosecution's lead medical expert, was the target of animosity on the part of one of the defense's medical experts. Additionally, several streetcar drivers claimed that the streetcars frequently arrived early, which tended to lessen the impact of the motormen's testimony that the defense called.

In the end, nobody seriously questioned the fact that Mary Phagan arrived at Leo Frank's office on April 26 in the afternoon, met her death in a matter of minutes, and then left. Before the scheduled arrival date of April 26, the English Avenue car carrying Matthews and Hollis arrived in town. In rebuttal, J.C. McEwing swore on behalf of the state.On April 26, he operated a streetcar between Marietta and Decatur Street. Hendricks' car was due there five minutes after the hour, Hollis and Matthews' car was due there seven minutes after the hour, English Avenue frequently cut off, White City car was due in town at twelve five minutes after the hour, and Cooper Street was due there seven minutes after the hour. The White City car is scheduled to arrive there prior to the English Avenue, five minutes after the hour, and seven minutes after the Cooper Street. In order to stop the Cooper Street car, the English Avenue car needed to arrive four to five minutes early.

On April 26, M.E. McCoy saw Mary Phagan in front of Cooledge's Place at 12 Forsyth Street and took the oath for the state in rebuttal. He headed straight down to Pencil Company, which is located south on Forsyth Street on the right side, after leaving the fork in the road at precisely 12:00. He took three or four minutes to get there, and when he arrived, he checked his watch to see what time it was. On April 26, in front of Cooledge's Place at 12 Forsyth Street, M.E. McCoy saw Mary Phagan and took oath for the state in rebuttal.

The most significant information in this text is that on April 26 around noon, George Kendley, a railroad employee, saw Mary Phagan. She was in sight as he rode the front end of the Hapeville car, which was scheduled to arrive in town at noon. The time that George Kendley saw her is just an estimate, but he did mention seeing her the following day to a number of people. Since he told several people that he would see her the following day, Mary Phagan should have arrived in town around ten minutes after leaving her house at ten to twelve.

It is only a guess that he saw her at that time, and his car was scheduled to arrive in town at that time. By learning of the tragedy the following day, the narrator is reminded of seeing Miss Haas. They were not questioned, so they did not provide testimony at the coroner's inquest. Since the tragedy, they have stopped abusing and demonizing Frank and refraining from making themselves a nuisance by bringing up his name while driving. They have discussed it with Mr. Brent, but they haven't indicated that, should he be set free, they'd join a group to help lynch him. They have discussed it with Mr. Leach, but they have not indicated that they would join a group to help lynch him if he escaped. Henry Hoffman, a streetcar company inspector, and N. Kelly, a motorman for the Georgia Railway and Power Company, is both sworn for the state in rebuttal. The streetcar company's inspector is Henry Hoffman, while The Georgia Railway and Power Company employs N. Kelly as a motorman. When they cut off the Fair Street car, Henry Hoffman was on Matthews' car and alerted him to the fact that he was moving too quickly. On April 26, N. Kelly could see the English Avenue car driven by Matthews and Mr. Hollis arrive at the corner of Forsyth and Marietta Street about three minutes after twelve. Mary Phagan may have exited the English Avenue car, but she didn't turn around. She wasn't in the English Avenue car. The speaker boarded a car at Broad and Marietta, then circled Hunter Street. These are the most crucial details in this document. Since they didn't want to become involved in it, the speaker chose not to address itf or the state's counterargument, W.B. Owens swore. The Georgia Railway and Electric Company's White City line, on which the speaker rode, has an arrival time of 12:05, two minutes before the English Avenue car.

At 12:55 on April 26, they arrived in town. After April 26, the speaker has noticed that the English Avenue car often arrives a minute or two before them. Defending the state was conductor on the English Avenue line Louis Ingram. He has repeatedly observed the car arrive early while working as a conductor on the English Avenue line. The most significant information in this text is that W. M. Matthews, the motorman and both W.C. Dobbs and the sergeant who conducted the Cross Examination were found not guilty of the crime in this court by the jury. During the state's refutation, W.M. Matthews and in rebuttal, W.C. Dobbs swore on behalf of the state. For a crime committed in this court, Matthews was found not guilty by the jury, while the jury in this court found W.C. Dobbs not guilty of the crime charged. W.W. Rogers was found not guilty of an offense in this court by the jury, whereas the jury exonerated W.M. Matthews from guilt in this court for an offense.

There was a pile of shavings where the chute came down on the basement floor, and the door to the pencil factory was securely fastened. The Private L.S. Dobbs team, including E.K. John Graham and J.W. Coleman swore for the state in rebuttal. Private L.S. Dobbs observed Mr. Rogers attempting to enter the back door leading up from the basement and rear factory on Sunday. In rebuttal, O. Tillander took the oath of the state. E.K. Graham responded by swearing on behalf of the state. In rebuttal, J.W. Coleman swore on behalf of the state. Mary Phagan's stepfather recalled speaking with Detective McWorth, who claimed to have found a "bloody club" and a portion of Mary Phagan's pay envelope on the first floor. The information pertaining to J's cross-examination is what is most significant in this text. Both J.M. Gantt and Ivy Jones. Ivy Jones and J.M. Gantt both took the oath on behalf of the state to refute the defence. Ivy Jones was in the saloon between the hours of 1:00 and 2:00 on April 26 when Jim Conley entered.

In further rebuttal, Harry Scott swore on behalf of the state. Jim Conley was last seen by Ivy Jones on April 26 at the intersection of Hunter and Forsyth Street, where she left him shortly after 2:00 a.m. Darley, according to Mr. Frank, is the embodiment of honor, so there is no point in asking questions about him. Ivy Jones informed him that they had reliable information indicating that Darley had been hanging out with other girls at the factory, that he was married, and that he had a family.

The two hours of cross examination were up. In just two or three minutes, L.T. Kendrick, a night watchman at the Pencil factory for two years, would punch the clocks for an entire night's worth of work. The dusty back staircase indicated that it had not been used recently. When Mr. Minar was questioned regarding when they last saw Mary Phagan, Vera Eps was present in the home. In June or July 1912, C.J. Maynard had seen Brutus Dalton enter the factory with a woman who weighed about 125 pounds.

Every morning, the clock was typically adjusted, and it occasionally ran slowly and occasionally quickly. W.T. Hollis swore on behalf of the state due to a confrontation for the state's rebuttal Every morning, the speaker rode with Mr. J.D. Reed. In rebuttal, J.D. Reed swore for the state. Mr. Hollis revealed to the speaker that Mary Phagan and George Epps were riding together and conversing like young lovers. In rebuttal, J.N. Stars swore for the state. Campbell and the narrator claimed that the detained Minola McKnight shortly after the murder in order to interview her.

Minola was transported to Mr. Dorsey's office by a bailiff, accompanied by a subpoena, and placed in a patrol wagon. A bailiff, a subpoena, and a patrol wagon were used to bring her to Mr. Dorsey's office and remove her from there. The most crucial information in this text is that the narrator saw Minola in the station house the following day and held her to get the truth. Minola was brought to Mr. Dorsey's office by a bailiff and placed in a patrol wagon in order to transfer her with maximum security. Mr. Dorsey assured the narrator that he could release her whenever he pleased and that he would do so if the chief deemed it appropriate. Dr. Clarence Johnson, an expert on gastrointestinal disorders, provided rebuttal testimony on behalf of the state. He is a physiologist who conducts his research on a living body as opposed to a dead body like a pathologist does. If a young child who eats a meal of bread and cabbage at 11:30 is discovered dead the following morning at 3:30 a.m. a rope around her neck, indentations where the flesh should have been, an eye bruise, blood on the back of her head, the tongue sticking out, blue skin—all signs that she died by being strangled—and her head bowed. The most crucial information in this text is that a pathologist takes her stomach a week or ten days after eating cabbage, declares exhibit G, finds starch granules that have not been digested, and finds 32 degrees hydrochloric acid.

Rigor mortise had been on her for 20 hours, and the blood had settled in her where gravity would. The digestion of the bread and cabbage was stopped an hour after eating them if the pathologist discovers that there was only combined hydrochloric acid and no abnormal condition of the stomach. Cross-examination is also required to look for head bruises, signs of strangulation, and other head injuries, as well as for anything that might impair blood flow or nerve function. Controlling the stomach, particularly the secretion, also helps to prevent the emergence of symptoms typical of normal digestion an hour after a meal. Absolute accuracy should be used when conducting the test.

It is generally accepted that the color test can be used to estimate how acidic a typical stomach is. Depending on the stomach's contents and the degree of acidity, the range is 30 to 45 degrees. Unless prevented by a preservative agent, formaldehyde has a neutralizing effect on the alkali present that eventually decomposes after death. If the stomach has disintegrated and the preservative has vanished, the hydrochloric acids in the stomach also disappear unless prevented by a preservative agent. Because of insufficient mastication, excessive juice dilution, or other factors that impair the mechanical effect, digestion can occasionally be delayed.

One of the most frequent causes of delayed digestion is insufficient mastication, along with drinking too much liquid fatigue. The layer, character, size, area of separation between, and arrangement of the layers below demonstrate indigestion in the cabbage defendants' exhibit 88. A scientific test must be performed on the stomach's workings, the length of time it spent there, and the presence and strength of the various acids. Dr. George M. Niles, who was sworn in as the state's representative in rebuttal, limits his research to digestive disorders. When Mary Phagan's body was discovered, there were indentations in her neck where a cord had been wrapped around her throat, proving that she had been strangled.

Her face was blown, her nails were broken, she had a small head wound, a tooth bruise on one of her eyes, and her body was discovered face down. The body had been in rigor mortise for 16 to 20 hours and was embalmed with formaldehyde-containing fluid. There was no inflammation, mucus, or obstruction preventing the contents from passing through the stomach normally. Undigested starch granules and 32 degrees of hydrochloric acid were present in the gastric juices. The pylorus was closed, and the gastric juices contained no dextrin, maltose, or free hydrochloric acid.

The pylorus was closed, and there was no restriction to the stomach's ability to empty itself. The pylorus was also closed, and there was no obstruction to the stomach's contents flowing out. For a considerable amount of time, the presence of hydrochloric acid in gastric juices does not alter their chemical makeup. The hydrochloric acid and gastric juices act as an antiseptic or preservative. When it comes to cross-examination of digestion, diseased stomachs vary greatly. You can quantify each stomach's capacity to break down any type of food using a mechanical rule. Every stomach has a specific time frame within which it must digest every type of food. Mastication is a crucial part of digestion, and not doing it causes starch digestion to be delayed.

Carbohydrates include both starch and cabbage. The most crucial information in this text is that if cabbage were consumed by a healthy individual but was not properly chewed, starch digestion would suffer, but the stomach would immediately become overworked. If the cabbage had been a live, healthy stomach and the digestive process had been running smoothly, it would have been completely broken down in four to five hours. Although she had chewed quite a bit, even if she hadn't completely masticated it, there should still be some saliva in her stomach. Chewing is largely a temperamental matter. Mary Phagan had a healthy stomach with a combined acidity of 32 degrees and no physical or mental obstructions to digestion. Dr. John Funk, a professor of pathology and bacteriologist, was shown sections from Mary Phagan's vaginal wall, which demonstrated torn epithelium walls at points immediately beneath that covering in the tissues below and blood infiltrated pressure. These sections demonstrated that the tissues below had areas where the epithelium wall had been torn off and blood pressure had infiltrated. Blood vessels that were further away from the point of rupture were not as heavily engorged as those that were close to the hemorrhage. The blood vessels that were further away from the torn point were not as engorged as those that were close to the hemorrhage. It is reasonable to assume that the swelling was brought on by the blood's pressure infiltration of the tissues.

A young woman between the ages of 13 and 14 is found with a cord around her neck, indented skin, cyanotic nails and flesh, the tongue protruding, and swollen blue nails—all signs that she had been strangled to death. These conditions must have been created prior to death because the blood could not have caused them. She was embalmed using a fluid that contained the typical amount of formaldehyde, and she will be removed from her grave in about a week or ten days. Her stomach contained undigested starch granules and cabbage similar to that in exhibit G, 32 degrees of combined hydrochloric acid, a closed pylorus, an empty duodenum, and 6 feet of small intestines. The uterus was also slightly enlarged, and the walls of the vagina showed dilation and swelling. Due to changes in the tissues and blood vessels below the epithelium covering, as well as the presence of blood, the epithelium was torn off prior to death.

Cross Examination: Last Saturday, Dr. Dorsey requested that the examiner look at the sections of the vaginal wall, so it is reasonable to assume that the digestion had advanced. The sections were 925 thousandths of an inch thick, about a quarter of an inch wide, and three quarters of an inch long. The autopsy was conducted without the examiner present, but the blood vessel changes indicated the reaction. The examiner served as Jim Conley in Dr. Wynn Owens' Sunday factory experiment while also being paid by the defense to help subpoena witnesses. The examiner overheard George Kendley express his resentment toward Leo Frank, saying that regardless of whether Leo Frank was guilty or not, someone had to be put to death for the murder of those streetcar drivers, and hanging one nigger was just as good as hanging another. Mr. M.E. Stahl, Miss C.S. Haas and N. Sinkovitz in sur-rebuttal swore for the defendant. Leo Frank was one of five or seven people who would get him, according to M.E. Stahl, who claimed that the conductor, George Kendley, had expressed his feelings toward Leo Frank. If the court cleared Frank, Kendley would be the next one to fall. 90% of the best people in the city believed that Frank was guilty and should be hanged, according to Miss C.S. Haas, who claimed that circumstantial evidence was the best kind of evidence to convict a man on. For the defense in rebuttal, N. Sinkovitz took the oath. He is a pawn broker and is familiar with M.E. McCoy, who recently gave him his watch as collateral.

A public-spirited citizen in 1913 Atlanta felt he should report to the authorities a single man who stated his opinion that Leo Frank was a "damned Jew" and should be hanged. This reveals a culture where such sentiments were scorned and even thought to be outside the bounds of socially acceptable conduct and expression. Leo Max Frank asked to address the court again in the closing moments of the trial, but he was not sworn in, was not sworn under oath, and was not subject to cross-examination. It was forbidden for Dorsey to ask him about it or use it as the basis for questions. The closing arguments made by both the prosecution and defense in the Leo M. Frank trial are the most significant details in this text.

Leo Frank insisted that any witnesses who claimed to have heard him refer to Mary Phagan by name were either lying or mistaken. At the conclusion of the trial, despite several of the young women under his supervision having just finished testifying, he did not spend even a brief moment repeating his claim that he never made lewd advances toward them. Despite this, he did not take the time to reiterate his claim that he never made lewd advances toward the young women under his supervision. We will discuss both the prosecution's and the defense's compelling closing arguments in the trial of Leo M. Frank in the up and coming audiobooks related to this tragic murder mystery.

🦠 WATCH CREDIT LINK 🦠

https://rumble.com/v240xx8-bre....t-weinstein-they-smu

May 2023

🔎 LEARN, READ, WATCH MORE 🔍

■ https://germs.truthparadigm.tv

■ https://germs.truthparadigm.news

#mRNA #Vaccines #Covid #Germs #C19

7 Digital Products you can create using AI

How to make money from AI? Jamie Interviews leading expert on profiting from AI - Part 4

Questo video è consigliato a tutta la cristianità desiderosa chè il fuoco della pentecoste possa continuare a bruciare nel proprio cuore.Buona Visione

THE LATE 1950s AND THE EARLY 1960s WAS THE AGE OF THE TEENAGE IDOLS, FRANKIE AVALON WAS ONE OF THEM. HERE IS A SONG BY FRANKIE AVALON (A BOY WITHOUT A GIRL) AND THE VERSION IN SPANISH BY LUIS BRAVO FROM CUBA.

Trump Wants Ukraine to Pay the Money Back

Elon Musk explains censorship stance in controversial Don Lemon interview.

The former CNN host pressed Musk on whether he has a “responsibility” to moderate peoples’ posts.

“I think we have a responsibility to adhere to the law,” Musk said, adding that if a post is illegal, “we’re going to take it down.”

To remove posts that didn’t break the law would mean “we’re putting our thumb on the scale or being censors.”..

'Racism Did It!' - Pete's Perfect Excuse For Latest American Bridge Blunder

The US Transport Sec blamed discriminatory planning for low-hanging bridges and underpasses, all designed to pick on people of colour.

It would give the owners of the Dali, which wrecked the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore on Tuesday, something to write down on the insurance claim....except the ship had a little accident in Antwerp, Belgium, in 2016 when it rammed a pier.

Pesky stationary objects, so racist!

Tucker Carlson - There is Systemic Racism in the United States, Against Whites. Everyone Knows It. N

Ep. 98 There is systemic racism in the United States, against whites. Everyone knows it. Nobody says it. How come?

Does Senator Pauline Hanson Really think she will Win More Votes for One Nation by Making Such State

❗"I'm standing up for the Jewish people. I'm sick of hearing about Palestinians. There is no genocide!"

🇦🇺🇵🇸🇮🇱Does Senator Pauline Hanson really think she will win more votes for One Nation by making such statements?

Ukrainian children are being turned into soldiers!

The Western media calmly reports about the "after-school training camps" where kids are learning to fight.

Source: https://t.me/AussieCossack/18886