Please donate now to help fund our work

The Murder Of Little Mary Phagan - Vanessa Neubauer - Chapter Twelve - Application For Pardon, 1983

The State Board of Pardons and Paroles received a formal request for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank in October 1982. The complaint was filed by the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Commission, and the Atlanta Jewish League, and was chaired by a panel of attorneys chaired by Atlanta immigration attorney Dale N. Schwartz. The Chamber of Commerce hopes to investigate the case with minimal outside pressure and publicity, and the plaintiffs have been working to file a pardon petition since Alonzo Mann gave his testimony. Dale Schwartz has publicly stated that the essence of seeking Leo Frank's pardon is to seek a formal rejection of anti-Semitism and bigotry, and to remove the obtrusive element to Georgia's history. Applicants are seeking a pardon based on additional legal concerns rather than the legality of Leo Frank's trial and conviction. The pardon effort, an AntiDefamation League staffer later stated, was not simply a matter of one person, not just the case of Leo Frank.

An official wrote the League's national The pardon effort for Leo Frank in the United States has been criticized for minimizing potential offense to blacks, repudiating prejudice against blacks and Jews, and reflecting Georgia's past as it reflected on the personal identity and regional pride of Georgians to do justice. The Atlanta Black Jewish Coalition has declared that they must seize this opportunity and the petition for pardon concluded, "Judgment, justice ye shall pursue." The pardon effort has been criticized for minimizing potential offense to blacks, repudiating prejudice against blacks and Jews, and reflecting Georgia's past as it reflected upon the personal identity and regional pride of Georgians to do justice. The petition for pardon concluded, "Judgment, justice ye shall pursue." Attorney Edgar Neely argued that the Georgia system of justice in 1913 impugned the reputation of its lawyers in general and particularly Frank's counsel. The leaders of the pardon effort responded at length, including outlining the new evidence of Alonzo Mann. Mobley Hall, chairman of the Amnesty and Parole Board at the time, weighed Mr Neely's claims.

He had four legal ways to acquit Leo Frank. Complexity by courts beginning with a governor's statement declaring Leo Frank not guilty, an order of the Georgia House of Representatives and/or Senate declaring Leo Frank not guilty, and an ad hoc motion for a retrial and pardon by the Georgia Commission procedure. Forgiveness and slogans. Governor Joseph Harris, District Attorney Louis Slayton, and the Georgia Senate all expressed sympathy for Leo Frank's efforts to acquit him and recommended that the Board of Pardons and Paroles seek a pardon. Petitioners began to think that a pardon would best meet the further legal purpose of Frank's acquittal and would be considered final by the public. Dale Schwartz pointed out that the public now understands the amnesty process as an exoneration, especially when it involves acquittal of the applicant. Petitioners also suggested that the court's ruling would make it appear that the Jewish community manipulated fellow judges.

The goal at the time was a pardon from the Amnesty and Parole Board. In a 1984 interview, Dale Schwartz told the editors of Israel Today that Georgia not only grants forgiveness for past crimes, but rather defendants are the type to seek state forgiveness for wrongful convictions. said he would grant a posthumous pardon.

The most important detail in this document is that of the petitioner for posthumous pardon in the Leo Frank case. The petitioners were personally involved in and affected by the incident, and their father suggested they contact the rest of the Phagan family. Their assessment of the family's opinion was correct, so the petitioners sent a letter to the parole board asking to allow the Phagan family to appear at the parole board hearing on the Leo Frank case. Last fall, the parole board received a formal written pardon request and was required to do so by order of the Georgia Senate dated March 26, 1982. The pardon request may be based on Alonzo Mann's 1982 testimony, but the Board is not limited to its consideration. Applicants are advised that the parole board does not plan to hold oral testimony hearings against anyone. The Phagans have requested that all information be provided in writing. The Commission is likely to make a decision later this year and has expressed its determination to base its decisions on the facts and evidence it desires to investigate the incident with minimal external pressure or public disclosure. are doing. Mr. Moore's letter confirmed the family's intuition that there would be some political involvement in the board, as well as their decision to consider posthumous clemency. On February 14, 1983, the Phagan family responded by letter to the board of directors. The letter said the alleged turmoil in court during the proceedings did not threaten the fairness of the proceedings or provide sufficient grounds to overturn the verdict. Trier's judge hearing the motion for retrial was right in believing that the jury whose impartiality was contested was competent. An important detail in this document is that Leo Frank was sentenced to death, which was commuted by Governor John Marshall Slayton. Governor Slayton said the jury's verdict would not be challenged if the commutation was granted, but the murder conviction would be commuted. Passed the state on the specified date. In August 1915, he was kidnapped by a mob from Mirageville State Facility and taken to Cobb County, where he was lynched. Alonzo Mann, 14, a witness in the Frank trial, received death threats and was not asked specific questions to prove Frank's innocence. Frank was competently represented by a council of great skill and experience. Alonzo Mann came forward to clear his conscience before his death, claiming that Leo Frank was not guilty of the murder of Mary Phagan, but provided no evidence to contradict Leo M. Frank's verdict. issued a statement swearing no. How long has he worked in the pencil factory? The Senate has asked the State Board of Amnesty and Parole to investigate the Leo Frank case. If the evidence points to Leo Frank's innocence, the Board should seriously consider granting Leo Frank a posthumous pardon. With no new evidence presented in 70 years, Mobley-Hall said he needed to fully prove his innocence with full evidence. The lawsuit is refiled every three to five years and will never be resolved.

The Phagan family demanded a copy of the applicant's application and all evidence presented, as well as information regarding future applications in the Leo M. Frank Mary Phagan case. On April 26, 1983, an article in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution reported that a pardon was being sought for Leo Frank. Atlanta Journal and Constitutional contributor Ron Mertz reported that the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Commission, and the Atlanta Jewish League have asked parolees and parole boards to reclaim Frank. . Celis Moore confirmed to reporters that her application for a posthumous pardon is under consideration, and this is the first time a posthumous pardon has been considered in Georgia. The petition contains 300 pages, including an affidavit from Alonzo Mann, who was Frank's clerk at the time of the murder, and a two-and-a-half-hour videotape of Mann drafting an affidavit protesting Frank's innocence. It contained evidence of The myth that formed around Leo Franck is based on Alonzo Mann's The Leo Franck Myth, which was attributed to Jim Conley as a confession, and secret evidence allegedly provided by John Slayton in 1915. formed public opinion about him long before he was born. Judge Arthur Pole hinted that Frank's innocence would one day come to light. The author is one of the few people who know that Frank was convicted and innocent of the lynching charges. After the trial was over and the Supreme Court upheld the conviction, he learned who murdered Mary Phagan, but that information could not be revealed as long as the particular person was alive. and arrived. Laws on this subject may or may not be wise laws, but some people think they are not wise laws.

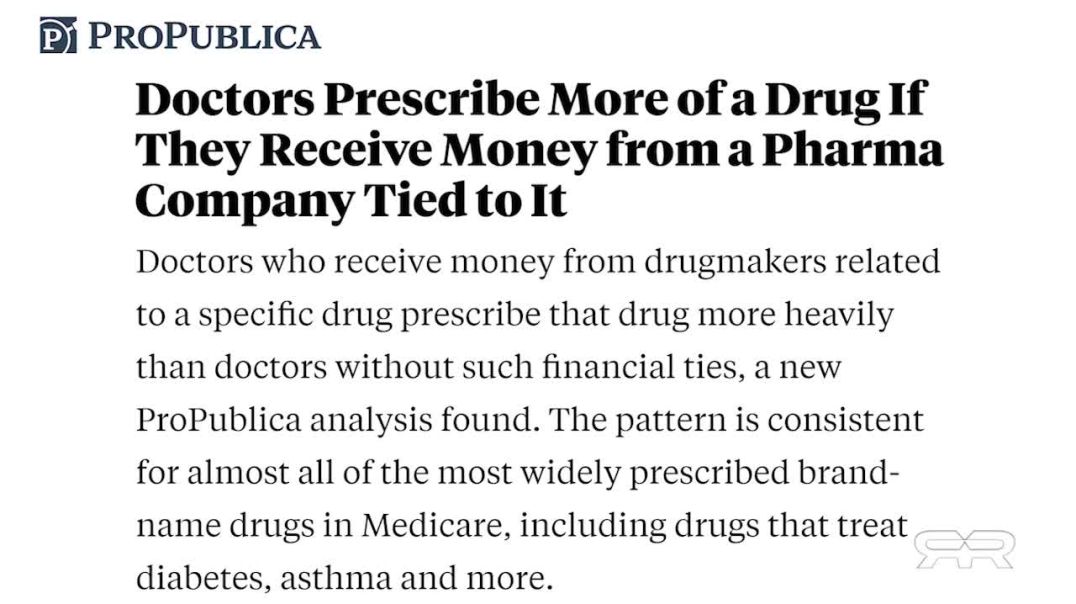

The most important details in this text are that the file to which he refers may have contained a confession obtained by Conley's own counsel, and that Alonzo Mann's testimony proved that Jim Conley, the state's chief witness against Frank, had lied on two counts. First, since Mann indicated Mary Phagan was alive as she was carried down, it contradicted Conley's statement that she was dead when he saw her on the second floor. The petitioners for the pardon were pinning their hopes on Alonzo Mann's testimony, which proved that Jim Conley, the state's chief witness against Frank, had lied on two counts first, since Mann indicated Mary Phagan was alive as she was carried down, contradicting Conley's statement that she was dead when he saw her on the second floor. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution felt that the case was compelling and that the Board of Pardons and Paroles should move quickly to clear Leo Frank's name and the enduring blot on the conscience of Georgia. Sherry Frank, Southeast area director of the American Jewish Committee, told the Journal that the pardon would white from the books the life sentence given Frank, but also clear him outright of guilt in Mary Phagan's killing. Anti-Defamation League Southeast Regional Director Stuart Lewinlove said he was seeking a full exoneration. Governor Joe Frank Harris has announced his intention to approve the pardon if recommended by the Board of Pardons and Parole. When the posthumous amnesty initiative became public, it itself provoked an anti-Semitic response.

On September 3, 1983, the New Order of Knights, a fringe clan group, held a march and rally in Marietta, Georgia, featuring signs reading no pardon for the Jew murderer Leo Frank. This was part of a conspiracy by a group called Christian Friends of Mary Phagan, who wrote to the pardon board to accuse and hopefully prove Christians guilty of prejudice, bigotry and antisemitism. Others felt the same way as the petitioners did, and the Atlanta Constitution had the power to right a great wrong and do a great good. Among those who extorted the board to pardon Leo Frank were a minister in Tennessee who felt that pardon would bring a sense of reassurance to many of the citizens who have been hurt and still suffer due to the prejudicial trial to which he was subjected many years ago, and a member of the Christian Council of Metropolitan Atlanta who viewed a pardon as a way to repudiate the twin evils of prejudice and mob rule. The Phagan family felt the same way, as they had known about the application for the posthumous par The narrator took a step to ensure that the next generation of the Phagan family would not be victimized by a newshungry press. They contacted Ron Mertz, who wrote the article about Mary Phagan, and told him of his mistake. He asked if the narrator would consider an article or series of articles about himself. A few months later, the narrator contacted the staff in Tennessee, telling him that he wanted to meet Alonzo Mann and asking if he could make arrangements. On July 19, the narrator met Alonzo Mann, Jerry Thompson, and Robert Sherborne at the narrator's home. The narrator was concerned that they were doing the right thing, but when he met Mr. Mann he knew they were doing the right thing. They spend an hour going through the narrator's huge scrapbook of the murder of Mary Phagan. The most important detail of this text is that of the relationship between the narrator and the witnesses to the murder of Mary Phagan. The narrator reads to the witness an article from Tennessee about a visit to the grave of the narrator's great-aunt, and the two become friends. The narrator then asks the witness to make more formal statements, such as where he was born, how long he said he lived in Atlanta, how long he worked for Mr. Frank, and whether he had met Mary Phagan. started asking questions. Finally, the narrator asked how long he had been working for Mr. Frank and whether he had seen her with her eyes. Finally, the narrator asked how long she had been working for Mr. Frank and if he had ever seen her. The narrator has been working at the pencil factory for several months, contradicting her father's view that Mr. Mann was only there for a week. The narrator noticed that Mr. Mann seemed tired and her voice was weakening. He recently had heart surgery and now wears a pacemaker. The narrator is 28 years old and has a heart condition. The narrator said that after meeting Jim Conley, he went home and told his mother what he had seen. When investigators arrived at her home, she asked when she had left.

The most important detail in the document is Mr. Mann's story and his attempt to get Leo Frank pardoned. Mr. Mann faced the challenge of publicizing and telling the world what he thought he had seen. He asked the author to tell the commission again that Leo Frank deserved a pardon, but the author felt it was impossible. On July 20th, the author received Thunderbolt #290 from the current Ku Klux Klan Society. He opposed any person or organization wishing to honor Little Mary Phagan, but he opposed any individual or organization using Little Mary Phagan's death to their own detriment. He wrote to the Anti-Defamation League in Atlanta and received a letter from Stuart Lewengrab that said: The KKK has reproduced Judge Randall Evans Jr.'s testimony from the May 15, 1983 Augusta Chronicle Herald on Leo Frank's appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the conviction, but Justices Fish and Beck disagreed on the admission of certain evidence. Frank then filed an extraordinary petition for a new trial with Supreme Court Justice Hill, which was denied, and on June 6, 1914, the Georgia Supreme Court unanimously upheld the decision. Frank then refiled his motion to reverse the judge's ruling against Hill, but the motion was denied. According to filings, two impartial Fulton County Superior Court judges, 12 impartial Fulton County jurors, and six impartial Georgia Supreme Court judges all confirmed that Leo Frank was legally tried and convicted. agreed to be sentenced to death by hanging. The Jewish community across the United States tried to defend Frank for being convicted because he was Jewish. An important detail of this document is that Governor John M. Slayton, on the last day of his presidency, commuted Leo Frank's sentence to life imprisonment, and accordingly applied the appropriate judicial policies established by the Fulton County Superior Court and the Supreme Court. It means that it was done. Stopped and overturned by Georgia. Much of the anger of Jewish communities across the country was directed at Thomas E. Kennedy. Thompson's Watson accused Watson of writing inflammatory articles to the Jeffersonian that contributed to Frank's conviction. The evidence was overwhelming, and Governor Slayton commuted Frank's sentence to life imprisonment, overturning and overturning due process established by the Fulton County Superior Court and the Georgia Supreme Court.

Much of the ire of Jewish communities across the country was directed at Thompson's Thomas E. Watson, who accused Watson of writing inflammatory articles in the Jeffersonian that contributed to Frank's conviction. A key detail in the document is that a new witness, Alonzo Mann, was first discovered and said he saw a black man with the body of Mary Phagan in the basement of the factory building. The archives department even wrote in one of its publications that the new evidence seemed to prove Frank's innocence. However, the authors point out that this is not new evidence and that during the trial it was revealed that Jim Conley carried the body to the basement. This correspondence is now part of the Archives Department. The suggestion that the governor or parole board can pardon the dead is utterly absurd.

The Constitution of Georgia provides that the legislative, judicial and executive powers shall remain separate and distinct. The Executive Department has no power to reverse, change, or wipe out a decision by the courts, albeit while the prisoner is in life, he may be pardoned, but a deceased party cannot be a party to legal proceedings. Pardon must be granted the principle upon his application or be evidenced by ratification of the application by his acceptance of it. It is too late now for any consideration to be given a pardon for Leo Frank, as pardon can only be granted to a person in life, not to a dead person. The author and his father were interested in the statements made by Judge Randall Evans, who had been told that the Phagan family were the only ones who had objected to a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank.

They felt that the judge made some important and relevant points, and they had to verify the statements concerning the pardon to find out whether the consideration of the application by the Board was indeed illegal. Mike Wing of the Pardons and Paroles Board was supportive of the author's request for a copy of the governing rules and consideration for a pardon. He learned that the application for pardon filed was indeed illegal and that there were only two instances in which a pardon could be granted according to the rules of the Board. On July 22, the author went to Nashville to meet the entire Tennesseeean staff, including John Segenthaler, the president and publisher, Jerry Thompson, Robert Sherbourne, and Sandra Roberts. On the wall of John Seagenthaler's office was a picture of the jury that convicted Leo Frank, which will remain there until a pardon is granted.

Mr. Segantholer said the staff was very cordial, courteous, and helpful to the author, and they shared their opinions, both pro and con, and remained strong in them. Mr. Segenthaler and the narrator discussed the possibility of a posthumous pardon, but Mr. Segenthaler felt that no complete proof of evidence could be submitted. The narrator realized that their opinions were as strong as their father's and that a posthumous pardon should not be granted unless there was complete proof of evidence. Later that evening, the staff allowed the narrator to go through Sandra's research files and determine what materials they would like to photocopy. Alonzo Mann called the narrator on July 26 to let him know he had received a letter from a Phagan and thought the narrator would be the most appropriate person to have it.

Frank Ritter of the Tennessean called the narrator on July 28 to ask him to let him know when they made a decision about going public. He added that no matter what, he supported the narrator.

Sandra Roberts called the narrator to a meeting with Bill Gronick, president of the American Jewish Committee, and Miles Alexander, an attorney, on August 3. They had concerns about the Phagan family and wanted the narrator to share their views. The narrator told them they didn't condemn or object to the Phagan family, but they objected to a pardon unless complete proof of evidence could be substantiated. They wanted to know how the narrator would deal with the situation if they were Leo Frank's great niece. On August 8, 1983, the narrator and her father met with Mike Wing of the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

The narrator drove to their parents' home in Decatur and they agreed to ride Marta, the rapid transit system in Atlanta. The narrator recollected stories and spoke of childhood memories, and the narrator expressed proud feelings for his father. The narrator was as proud of the narrator as he was of the narrator. Celis Moore and Mike Wing met at 02:00 p.m. and discussed the idea of a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank.

Moore informed Mike that the Phagan family was opposed to the granting of a posthumous pardon because there was no absolute proof of Frank's innocence. He felt that Alonzo Mann's affidavit offered no proof, but was merely Mann's opinion that Frank did not commit the murder. Moore also pointed out that those who were seeking the pardon chose to impose today's judicial standards for a trial that occurred in 1913. Moore felt that any person or organization could and should have the right to pay little Mary Phagan tribute as long as it wasn't for their own prejudicial purposes. Mike told them that Judge Randall Evans, Jr., who was quoted in the Thunderbolt, was not a member of the Klan and felt that the courts of Georgia should be upheld in dealing with the Leo Frank case.

Edgar Neely, the attorney who also opposed the pardon, was also present. The most important details in this text are the events leading up to the application for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank. On August 9, 1983, Edgar Neely wrote a letter to the board stating his opposition to the pardon. On August 20, 1983, the author decided to acknowledge their name and legacy to the press. On September 1, the Marietta Daily Journal reported that the Pardons and Paroles Board should reconsider the case, and Governor Harris was quoted as saying that the case deserves reconsideration. Governor Harris did not say whether he would recommend a posthumous pardon for Frank.

Dr. Ku Klux Klan's new leader, Edward Fields of Marietta, has planned a KKK march from Marietta Square to Mary Phagan's grave on Saturday, September 3rd. About 100 to 150 members of the family were expected to attend a service in memory of Mary Phagan. Marietta Mayor Bob Fronoy announced that a service for those opposed to the KKK rally would be held at First Baptist Church at 148 Church Street in Marietta. On Sept. 5, Tennessee state officials Frank Ritter, Sandra Roberts, and photographer Pat Casey arrived at the author's home, grilled hot dogs and hamburgers outside, and began the interview. . The author's father did most of the talking, and the rest of the family listened intently. When he read the inscription, he was overwhelmed with emotion and cried. His tears made the author cry. The story of Tennessee's "Little Mary Phagan Can't Be Forgotten" is written honestly, concisely, and with a sensitive feeling towards the author. On September 7, Darwood McAllister of the Atlanta Journal wrote an editorial statement on the Frank case. He considered the Klan march a futile attempt to ensure the survival of the Klan, and used the posthumous pardon of Leo Frank as an excuse. He also said that 10 years after the murder, journalists of the Atlantic Constitution found new evidence pointing to Frank's innocence. But prominent Atlanta Jews persuaded newspapers to withhold the story, fearing it would have new repercussions. The author and his father contacted the journal's Ron Mertz and told him they were ready to go public in Georgia. On September 14, the Atlanta Journal published a letter from Randall Evans, Jr. in response to McAllister's editorial opinion. The article reminded readers that Georgia law has no authority to pardon the dead. Justice Evans succinctly expressed his views in response to Darwood McAllister's statement. The story of Ron Mertz, published in the Atlanta Journal on September 22, 1983, represented a step forward for the Phagan family, but one that prevented them from going backwards. On September 20, 783, the Board of Directors allowed the Phagan family to speak on the Board, including Mobley Hall Chairman Mamie Reese, James Morris, Michael Wing, and Wayne Snow, Jr. was The Board of Directors did not know of the existence of the Phagans until they received a report from Mike Wing. They were concerned about the feelings of the Phagan family and felt they could share that with the entire board.

James Phagan and Mary Phagan are direct descendants of Little Mary Phagan. They came to share their views and opinions on the posthumous pardon request for Leo Frank, who was convicted of the murder of Little Mary Phagan. Due to the large number of articles, editorials and opinions published by both the newspaper and television stations, and external pressure from the Senate, the newspaper allowed an interview with Atlanta Journal contributor Ron Mertz. They are concerned that they will be granted a posthumous pardon, and if they can find evidence in court to prove Leo Frank's innocence in the murder of Little Mary Phagan, they will be willing to come forward and let the world know.

The foremost critical subtle elements in this content are the occasions encompassing the lynching of Leo Straight to the point in 1983. On December 22, 1983, the Board of Pardons and Paroles reported its choice, which weighed intensely on the author's intellect within the taking after months. Amid that time, the Modern York Times, Washington Post and US magazine sent correspondents to meet the creator and her father, and one of the columnists told the creator through and through that their granddad and father had been lying which Leo Straight to the point was guiltless. On December 23, 1983, the author's father went to the state capitol building where the board was to report its choice. When they arrived at Bernard's guardians domestic, Bernard's mother couldn't hold up to tell the creator that the ask for a after death exculpate for Leo Straight to the point had been denied.

The author's father had cleared out Atlanta that morning for Michigan to spend Christmas with Bernard's family, and when they arrived, Bernard's mother couldn't hold up to tell the creator that the ask for a after death exculpate for Leo Straight to the point had been denied. The Leo Straight to the point case was a riddle 70 a long time after it started. The board had organized an examination staff beneath the direction of Chairman Celis Moore and displayed prove such as daily paper accounts, the trial brief, books and letters, at the side brief outlines. Alonzo Mann's declaration was the primary to be assessed, but the board felt it only cast question on Jim Conley's declaration. The board set around to recreate something that happened 70 a long time back, but all the performing artists were expired but Alonzo Mann.

No other witnesses showed up, no one uncovered up to this time mystery fabric, and there was no concrete prove of a confession by Jim Conley. In spite of the entry of time, the Leo Straight to the point case remained a riddle. The foremost vital points of interest in this content are that Leo M. Straight to the point was found blameworthy in Fulton Province Prevalent Court of the kill of Mary Phagan on Admirable 25. The Board of Pardons and Paroles announced that the lynching of Leo Straight to the point and the truth that no one was brought to equity for that wrongdoing could be a recolor upon the state of Georgia which allowing a after death acquit cannot remove. The Board moreover announced that the lynching of Leo Straight to the point and the truth that no one was brought to equity for that wrongdoing may be a recolor upon the state of Georgia which allowing a after death acquit cannot expel.

The Board moreover announced that the lynching of Leo Frank and the truth that no one was brought to equity for that wrongdoing may be a recolor upon the state of Georgia which allowing a after death acquit cannot evacuate. Leo M. Straight to the point was sentenced to passing by hanging for nearly two a long time and was requested to the most noteworthy levels within the state and government court framework. On June 21, 915, senator John M. Slayton commuted the sentence of passing to life detainment. On Eminent 17, 1915, a gather of men took Leo M. Straight to the point by drive from the state jail at Millageville, transported him to Cobb District, Georgia, and lynched him. On January 4, 1983, the Board gotten an application from the AntiDefamation Association of Bennet Brith, the American Jewish Committee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation, Incorporated, asking a full acquit excusing Leo M. Frank straight to the point of blame of the offense of killing someone (first degree murder).

The court granted the petitioners a full pardon, and the only basis for exoneration of the murders for which Leo M. Frank was convicted was conclusive evidence that Frank was innocent. recommended. The burden of proof on this is on the applicant.

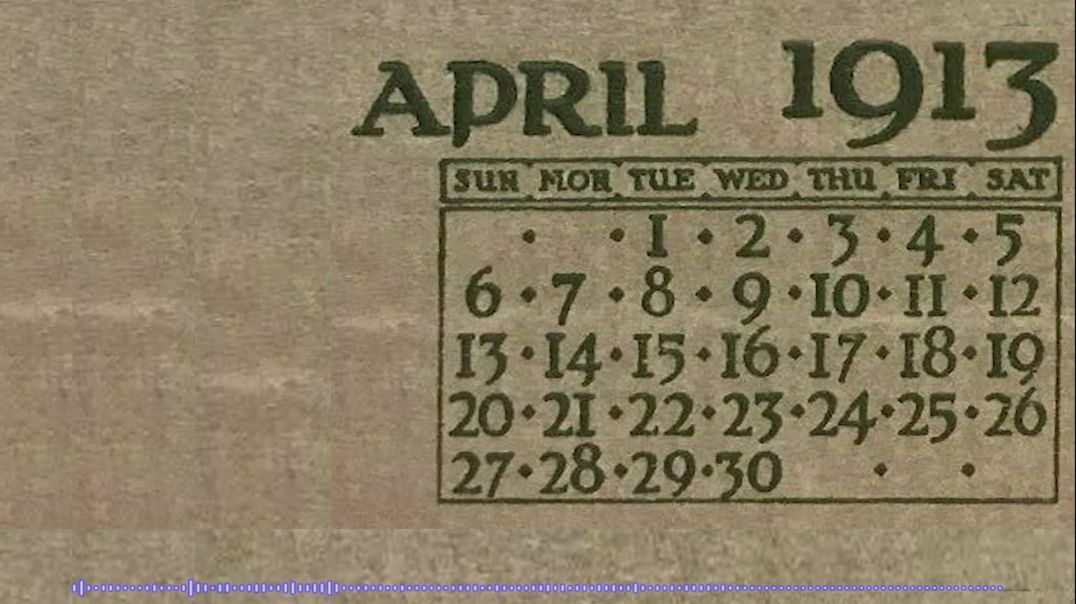

The information submitted to the parole board in this matter is considerable. The affidavit of Alonzo Mann, dated March 4, 1982, is accompanied by numerous other documents submitted in support of the pardon. Mann made statements to journalists Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherbourne, which were videotaped and recorded by a court reporter in the presence of representatives of the parole board. Mann's major point was that upon reentering the front door of the National Pencil Company building on April 26, 1913, he saw the limp form of a young girl in the arms of Jim Conley on the first floor. Governor Slayton concluded that the elevator was not used to transport the body of Mary Phagan to the basement.

Briefs have been submitted in opposition to the pardon, citing evidence and information to support that view, and letters have been received reflecting opinions in support of and in opposition to the pardon. The brief of trial evidence obtained from the Supreme Court of Georgia contains all the testimony given at the trial, which is the foundation upon which most arguments on both sides of the issue are based. The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for that crime is a stain upon the State of Georgia which, granting a posthumous pardon cannot remove. 70 years have passed since the crime was committed, and no principals or witnesses, with the exception of Alonzo Mann, are still living. After an exhaustive review and many hours of deliberation, it is impossible to decide conclusively the guilt or innocence of Leo M. Frank.

For the Board to grant such a pardon, the innocence of the subject must be shown conclusively. Therefore, the Board hereby denies the application for a posthumous pardon for Leo M. Frank. Dale Schwartz had declared Alonzo Mann's testimony credible, but the board members doubted its value as concrete evidence. Even if Jim Conley had lied, the board argued, it did not mean that Frank was innocent. The pardon application for Leo Frank was motivated by extra legal goals, but it also spoke of the pardon process as within the structure of the judicial process.

The application cited federal court cases to justify standing to seek a pardon. The petitioners, in attempting to repudiate antisemitism, represented their attempt as a legal effort to repudiate the libel against the Atlanta Jewish community and injury. The conclusion of the pardon application read, "The public good will be served, a historic injustice will be corrected, a 70 year libel against the Jewish community of Georgia will finally be set aside, and the soul of Leo Frank will at last rest in peace." The evidence in Man's testimony and the collective weight of people believed in Frank's innocence in 1915 provided the claim for Frank's innocence. However, the leaders of the pardon effort tied the extra legal justifications for the pardon and their procedural mindset very tightly together, leading to claims of innocence that were not easily justified. Dale Schwartz publicly responded to the passage in the board's statement which said that Frank's innocence was not proved beyond any doubt, yet the pardon application itself stated that Leo Frank was innocent to a mathematical certainty.

The response to the board's denial of pardon was immediate and vociferous, with the Atlanta Constitution running an editorial cartoon showing three men labeled as board members packing away a crate. Television and radio broadcasters took up the cry, as did the three groups who had filed for the posthumous pardon. Board members, convinced of the sincerity of their investigation and decision, also proclaimed themselves in shock. Hundreds of letters criticizing the decision came into the board weekly, but the author felt that the board made a fair decision from the start.

The information submitted to the parole board in this matter is important. Alonzo Mann's March 4, 1982 affidavit is accompanied by a number of other documents submitted in support of the pardon. Mr. Mann made statements to journalists Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, which were videotaped by court reporters in the presence of parole board officials. Mann's point is that when he re-entered the front door of the National Pencil Company building on April 26, 1913, he saw a limp little girl on the ground floor in Jim Conley's arms. Met. Governor Slayton concluded that the elevator was not used to transport Mary Phagan's body to the basement. Petitions were filed against the amnesty, citing evidence and information to support its views, and letters were received expressing opinions in favor of and against the amnesty. Evidence obtained from the Georgia Supreme Court includes all statements made during the trial and is the basis for most of the discussion on both sides of the issue. The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for his crimes is a stain on Georgia that his posthumous pardon will not remove. Seventy years have passed since the incident occurred, and with the exception of Alonzo Mann, there are no main culprits or witnesses alive. After extensive research and hours of deliberation, it is impossible to conclusively determine the guilt or innocence of Leo M. Justin. Frank.

In order for a court to grant such a pardon, the innocence of those involved must be conclusively proven. Accordingly, the Commission hereby denies the claim for posthumous pardon against Leo M. Frank. While Dale Schwartz said Alonzo Mann's testimony was credible, board members questioned its value as concrete evidence. The board argued that even if Jim Conley lied, it didn't mean Frank was innocent. Leo Franck's pardon request was motivated by an additional legal purpose, but it also referred to the pardon process as part of the structure of the court process.

The lawsuit cited federal court cases to justify eligibility for amnesty. Petitioners presented their attempt to reject anti-Semitism as a legal attempt to reject defamation and infringement of Atlanta's Jewish community. The conclusion of the pardon petition is that "the public interest will be realized, historical injustice will be righted, 70 years of defamation against Georgia's Jewish community will finally be shelved, and Leo Frank's soul will finally rest." was written. The combined weight of human testimony evidence and those who believed Frank's innocence in 1915 supported Frank's claims of innocence. However, the leaders of the amnesty effort have so closely associated additional legal justifications and procedural ideas for pardons that they have resulted in claims of innocence that are not easily substantiated. Dale Schwartz publicly reacted to passages in the commission's statement that Frank's innocence had not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt, but the pardon petition itself was written by Leo Frank with mathematical certainty. said he was innocent.

The response to the board's pardon refusal was immediate and vocal, with the Atlanta Constitution running an editorial cartoon depicting three men nominated for board membership packing a box. Television and radio stations responded to the call, as did the three groups that had sought posthumous amnesty.

The information submitted to the parole board in this matter is important. Alonzo Mann's March 4, 1982 affidavit is accompanied by a number of other documents submitted in support of the pardon. Mr. Mann made statements to journalists Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, which were videotaped by court reporters in the presence of parole board officials. Mann's point is that when he re-entered the front door of the National Pencil Company building on April 26, 1913, he saw a limp little girl on the ground floor in Jim Conley's arms. Met. Governor Slayton concluded that the elevator was not used to transport Mary Phagan's body to the basement. Petitions were filed against the amnesty, citing evidence and information to support its views, and letters were received expressing opinions in favor of and against the amnesty. Evidence obtained from the Georgia Supreme Court includes all statements made during the trial and is the basis for most of the arguments on both sides of the issue. The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for his crimes is a stain on Georgia that his posthumous pardon will not remove. Seventy years have passed since the incident, and with the exception of Alonzo Mann, none of the clients or witnesses have survived. After extensive research and hours of deliberation, it is impossible to conclusively determine the guilt or innocence of Leo M. Justin. Frank.

In order for a court to grant such a pardon, the innocence of those involved must be conclusively proven. Accordingly, the Commission hereby denies the claim for posthumous pardon against Leo M. Frank. While Dale Schwartz said Alonzo Mann's testimony was credible, board members questioned its value as concrete evidence. The board argued that even if Jim Conley lied, it didn't mean Frank was innocent. Leo Frank's pardon request was motivated by an additional legal purpose, but it also touched on the pardon process as part of the structure of the court process.

The lawsuit cited federal court cases to justify eligibility for amnesty. Petitioners presented their attempt to reject anti-Semitism as a legal attempt to reject defamation and infringement of Atlanta's Jewish community. The pardon petition concludes: "The common good is done, historic injustices are righted, 70 years of defamation against Georgia's Jewish community is finally shelved, and Leo Frank's soul is finally at rest. Let's go" was written. The combined weight of human testimony evidence and those who believed Frank's innocence in 1915 supported Frank's claims of innocence. However, the leaders of the amnesty effort have so closely associated additional legal justifications and procedural ideas for pardons that they have resulted in claims of innocence that are not easily substantiated. Dale Schwartz publicly responded to passages in the House Opinion that said Frank's innocence had not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt, but the pardon petition itself held that Leo Frank was mathematically innocent The information submitted to the parole board in this matter is important. Alonzo Mann's March 4, 1982 affidavit is accompanied by a number of other documents submitted in support of the pardon. Mr. Mann made statements to journalists Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, which were videotaped by court reporters in the presence of parole board officials. Mann's point is that when he re-entered the front door of the National Pencil Company building on April 26, 1913, he saw a limp little girl on the ground floor in Jim Conley's arms. Met. Governor Slayton concluded that the elevator was not used to transport Mary Phagan's body to the basement. Petitions were filed against the amnesty, citing evidence and information to support its views, and letters were received expressing opinions in favor of and against the amnesty. Evidence obtained from the Georgia Supreme Court includes all statements made during the trial and is the basis for most of the arguments on both sides of the issue. The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for his crimes is a stain on Georgia that his posthumous pardon will not remove. Seventy years have passed since the incident, and with the exception of Alonzo Mann, none of the clients or witnesses have survived. After extensive research and hours of deliberation, it is impossible to conclusively determine the guilt or innocence of Leo M. Justin. Frank.

In order for a court to grant such a pardon, the innocence of those involved must be conclusively proven. Accordingly, the Commission hereby denies the claim for posthumous pardon against Leo M. Frank. While Dale Schwartz said Alonzo Mann's testimony was credible, board members questioned its value as concrete evidence. The board argued that even if Jim Conley lied, it didn't mean Frank was innocent. Leo Frank's pardon request was motivated by an additional legal purpose, but it also touched on the pardon process as part of the structure of the court process.

The lawsuit cited federal court cases to justify eligibility for amnesty. Petitioners presented their attempt to reject anti-Semitism as a legal attempt to reject defamation and infringement of Atlanta's Jewish community. The pardon petition concludes: "The common good is done, historic injustices are righted, 70 years of defamation against Georgia's Jewish community is finally shelved, and Leo Frank's soul is finally at rest. Let's go" was written. The combined weight of human testimony evidence and those who believed Frank's innocence in 1915 supported Frank's claims of innocence. However, the leaders of the amnesty effort have so closely associated additional legal justifications and procedural ideas for pardons that they have resulted in claims of innocence that are not easily substantiated. Dale Schwartz publicly responded to passages in the House Opinion that said Frank's innocence had not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt, but the pardon petition itself held that Leo Frank was innocent with an absolute certainty.

The response to the Board's refusal to pardon was immediate and vocal, with the Atlanta Constitution running an editorial cartoon depicting three men nominated for Board membership packing a box. Television and radio stations responded to the call, as did the three groups that had sought posthumous amnesty. Board members who were convinced of the seriousness of the investigation and decision were also shocked. Although I received hundreds of letters every week criticizing the decision, I felt that the Board had made a fair decision from the beginning.

The court said complete and fresh evidence had to be presented before a posthumous pardon could be granted. Alonzo Mann's testimony was not new evidence and did not prove that Leo Frank did not murder young Mary Phagan. The Atlanta Journal said the state of Georgia refused to clear Leo Frank's name, which is not true. There are plenty of people in Georgia who have no relationship with Mary Phagan, are not fanatics, and find Leo Frank guilty. The author's father petitioned the local television station to refute Zeit's editorial statement regarding the amnesty, but was denied. That phase is over for the rest of the world, not the author's family. The denial of a posthumous pardon was only a temporary respite, and the horror show continued.