Please donate now to help fund our work

- Film & Animation

- Music

- Pets & Animals

- Sports

- Travel & Events

- Gaming

- People & Blogs

- Comedy

- Entertainment

- News & Politics

- How-to & Style

- Non-profits & Activism

- McIntyre Report

- Jamie McIntyre uncensored

- RAW Report

- Candace Owens

- Steve Kirsch

- Tucker

- Bongino

- Elon musks

- Alan Jones Australia

- RT News

- Wayne Crouch Show

- Other

The Murder Of Little Mary Phagan - Vanessa Neubauer - Chapter Six - Sentencing And Aftermath

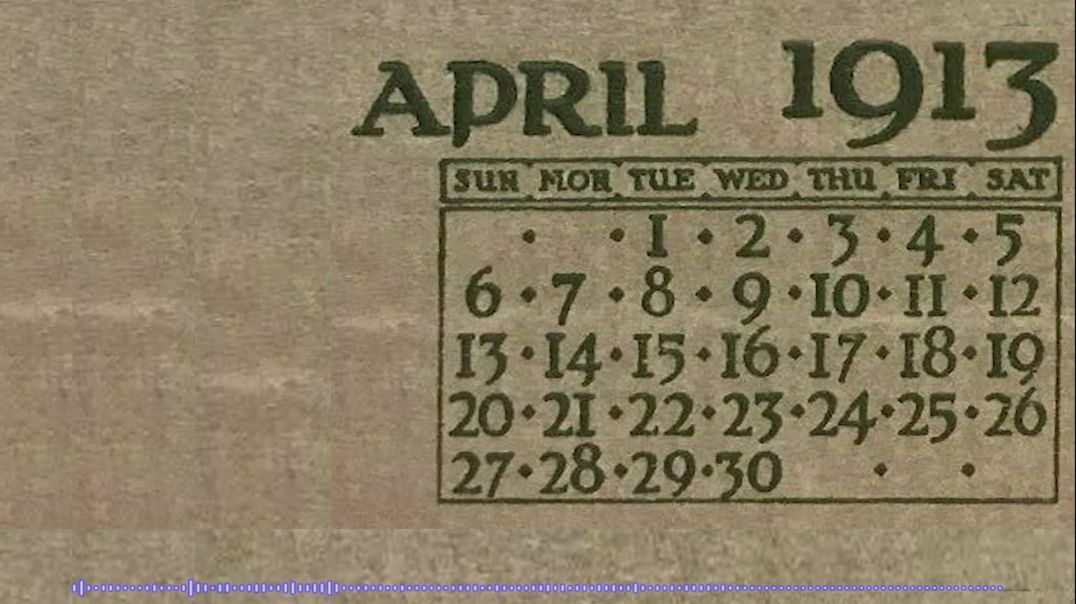

The most important details in this text are the sentencing and aftermath of Leo Frank's trial. Judge Roan secretly brought Frank and the other principals together in the courtroom for the formal sentencing. The sentence read, "Leo M. Frank be taken from the bar of this court to the common jail of the county of Fulton and be safely there kept until his final execution in the manner fixed by law." On the 10th day of October 1913, the defendant was executed by the sheriff of Fulton County in private, witnessed only by the executing officer, a sufficient guard the relatives of such defendant and such clergyman and friends as he may desire, and that the defendant, between the hours of 10:00 A.m. and 02:00 p.m., be by the sheriff of Fulton County hanged by the neck until he shall be dead and may God have mercy on his soul." The trial had been the longest and most expensive trial in Georgia history, with the stenographic record being 1,080,060 words. The state star witness, Jim Conley, had been on the witness stand longer than any other witness in state history Judge Roan was Rosser's senior law partner from 1883 to 1886. The temper of the public mind was such that it invaded the courtroom and made itself manifest at every turn the jury made. This prejudice rendered any other verdict impossible. Frank's lawyers began to prepare their appeal immediately after the sentencing, including affidavits about the alleged prejudice towards Leo Frank of two members of the jury, A. H. Hensley and M. Johanning. The family of H. C. Lovenhard swore that on meeting Marcellus Johenning on the street before the trial he had told them, "I know he is guilty". Other points raised included the jurors being influenced by the crowd's demonstrations outside the courtroom and that the evidence did not support the verdict. Solicitor General Dorsey argued that the trial had been fair and countered with affidavits from eleven jurors who swore they did not hear or see demonstrations from crowds outside the courtroom. Both jurors who had been deemed prejudiced by the defense denied the charges. Rosser and Arnold made a final plea to Judge Roan, who denied the defense's motion for a new trial. The ruling was affirmed by the Georgia Supreme Court on February 17, 1914. Two judges, Beck and Fish, dissented on the question of admissibility of Jim Conley's testimony as to Frank's sexual perversion, but did not find the evidence in question sufficient cause to alter the guilty verdict. Not long after the Georgia Supreme Court decision, the Atlanta Journal reported that the state biologist who examined the body of Mary Phagan had concluded that the hair found on the lathe which the prosecution had cited as a major factor in its case, was not Mary Phagan's. The biologist told Solicitor General Dorsey that he did not depend on the biologist's testimony, as other witnesses in the case swore that the hair was that of Mary Phagan. The most important details in this text are that several prosecution witnesses retracted their original testimony, including Albert McKnight, Mrs. Nina Formby, George Epps, Jr., and Mary Phagan. Other witnesses conveyed that they had invented or lied about evidence due to the pressure brought by police detectives and solicitor Dorsey. In addition, the defense lawyers restudied the case, including Henry Alexander, who studied the murder notes allegedly written by Conley at Frank's direction, which were written on old carbon pads and had a dateline of September 19.

Mr. Alexander alleged that the words "night witch" in the note beside Mary Phagan's body, which had been interpreted to mean night watch or watchman by those who believed the notes had been written under the direction of a white man, actually referred to a negro folktale. On March 7, 1914, Frank was resentenced to die. A stay of execution was obtained on an extraordinary motion for a new trial based on newly found evidence. Three witnesses said the state's star witness, Jim Conley, was the killer. Annie Maud Carter in New Orleans said Conley told her he had called Mary Phagan over as she left Frank's office with her pay envelope, hit her over the head, and pushed her over a scuttle hole in the back of the building.

The most important details in this text are that Annie Maud Carter gave the Burns Agency some love letters from Conley which the Constitution said were so vile and vulgar that they couldn't be published in the newspaper. The defense contended that these love letters showed that Conley had perverted passion and lust. A black prisoner named Freeman told his story to the prison doctor, who reported that Conley was the killer. Conley's court appointed attorney, William Smith, thought Frank was innocent and made a public statement on October 2,114, saying that Conley's testimony was a cunning fabrication. This extraordinary revelation, which went against the lawyer client confidentiality privilege, was extolled by those who believed in Frank's innocence and castigated as being caused by bribery by those who believed him guilty.

William Smith revealed no new facts to support his beliefs, but instead tried to show how the already known facts had been misinterpreted due to Conley's lies. It has been said that Jim Conley confessed to William Smith, and a confession statement allegedly by Conley has been published in For One confessions of a Criminal Lawyer by Alan Lumpkin Henson. However, Walter Smith, William Smith's son, denied the authenticity of Conley's "confession", but brought to light facts which had been previously undisclosed regarding William Smith's relationship to his client. William Smith was reputed to be a very conscientious and ethical lawyer, and his prime obligation was to his client. He had been appointed to defend Conley by the court and he worked very closely with the prosecutor, Hugh Dorsey.

Smith believed in Frank's guilt and coached Jim Conley in how to react in the courtroom. He acted out the style and gyrations of Luther Rosser to Conley so well that when the actual trial was in session, Conley was not rattled in the least. Smith went to great lengths to defend Conley and to dig up facts against Frank. At some point in the course of the trial, Smith began to doubt that his client had been telling the truth and tried to get him the lightest sentence possible. Conley was convicted as an accessory to the fact and sentenced to one year on the chain gang. Smith felt morally and legally free to do some investigating and probing on his own.

William Smith believed that Leo Frank was innocent and that he himself was responsible for his conviction. He launched a thorough investigation which convinced him that Frank was innocent and that Conley was guilty. He went to Governor Slayton with his conclusions and his story was important in helping Slayton reach the decision to commute Frank's sentence. Smith's life was threatened and he and his family were forced to leave Georgia. In the last years of his life, Smith's vocal cords were paralyzed and he carried a pad of paper on which to write messages in the hospital room.

On May 8, 1914, superior court Judge Ben H.Hill denied the defense motion for a new trial, which was affirmed unanimously by the Georgia Supreme Court. Jewish organizations and groups raised the issue of religious prejudice before Leo Frank's trial ended. The appeals for funds for Leo Frank's defense were made through mailing, circulars and newspaper advertisements throughout the country and particularly in the north. This resulted in a virtual reenactment of the Civil War between Northern and southern newspapers, which increased in intensity as the trial progressed. The New York Times and Colliers Weekly called for a new trial, mass rallies were held in United States cities, and thousands of letters, petitions and telegrams were sent to Governor Slayton and soon to be Governor Nat Harris.

However, the conviction of Frank became an article of faith for Southerners and the belief in Frank's innocence became the litmus test in the Jewish community of Atlanta for antisemitism. On March 10, 1914, the Atlanta Journal editorially called for a new trial, saying that if Frank is found guilty after a fair trial, he should be hanged and his death without a fair trial and legal conviction will amount to judicial murder. The most important details in this text are that the court, lawyers, and jury were not able to decide impartially and without fear the guilt or innocence of an accused man. The atmosphere of the courtroom was charged with an electric current of indignation, and the streets were filled with an angry, determined crowd ready to seize the defendant if the jury had found him not guilty. When the jury returned the guilty verdict, Frank was not in the courtroom, but at the Fulton Tower.

Cheers for the prosecuting counsel were irrepressible in the courtroom throughout the trial, and on the streets, unseemly demonstrations and condemnation of Frank were heard by the judge and jury. The judge was powerless to prevent these outbursts in the courtroom and the police were unable to control the crowd outside. The Fifth Regiment of the National Guard was kept under arms throughout the night, ready to rush on a moment's warning to the protection of the defendant. The press of the city united in an earnest request to the presiding judge to not permit the verdict of the jury to be received on Saturday, as it was known that a verdict of acquittal would cause a riot. Frank was tried and convicted, but the evidence on which he was convicted is not clear.

The outbursts in the courtroom and the police were unable to control the crowds outside were events that all three newspapers had not printed during the trial. The Journal remained quiet about these events for a year.

The Atlanta Georgian, which was silent during the trial, later called for a new trial. Tom Watson, who had been defeated for vice president of the United States on the populace ticket in 1896, immediately launched a scathing attack against those criticizing the results of the Frank case. He referred to Frank as being a Jew pervert and said he denied justice to the family of a poor factory girl. Burns offered a $1000 reward to anyone who could provide evidence that Frank was a sexual pervert, but no one came forward. Burns also brought forth evidence given to him by the reverend C.B.Ragsdale, pastor of the Atlanta Baptist Church, who told the story of overhearing two black men, one of whom confessed to killing a little girl at the factory the other day. Later, Ragsdale repudiated his statement. A Burns operative, Mr. Toby, had been retained by members of the Phagan family and their neighbors to investigate the murder and discover the murderer. After several weeks of investigating, Toby resigned and announced that he had concluded that Frank was the guilty party. Dorsey alleged that Burns tried to bribe witnesses to give false testimony.

The hearing on extraordinary motion for a new trial was based on the absence of Frank at the reception of the verdict. On December 7, 1914, a writ of error was taken to the United States Supreme Court and was denied. Frank was sentenced to be hanged on January 22, 1915. Frank's attorneys then filed an application for a writ of habeas corpus to the United States Supreme Court on April 19, 1915. The two justices who dissented were Oliver Wendell Holmes and Charles Evans Hughes.

They dissented on the basis that a lower court hearing should have been held to determine the validity of the defense. The most important details in this text are that Governor John Slayton was the only hope left for Frank, and his attorneys appealed to him for a commutation of his sentence from hanging to life imprisonment. Slayton referred this request to the state Prison Commission and asked them to pass their recommendation to the governor. Meanwhile, Frank's attorneys filed an appeal for a clemency hearing before the three man Georgia Prison Commission. The hearing date was scheduled for May 31, 1915.

On May 31, 1915, out of state and in state delegations appeared to plead for Frank's life. They had submitted voluminous documents to convince the commission an error had been made, including a letter by presiding Judge Leonard Roan written shortly before his death on March 23, 1915. Some members of Roan's family doubted the authenticity of the letter for years, but Dr. Wallace E. Brown, owner of the Berkshire Hills Sanatorium, attested to Roan's rational mental state. Brown also stated that he has been a resident of North Adams, Massachusetts, practically all his life, and is now serving his third term as mayor of the city of North Adams.

On Sunday, November 20, 1914, Judge L.S. Roan of Atlanta, Georgia dictated a letter to Mrs. Wallace E.Brown of North Adams, Massachusetts, asking for executive clemency in the punishment of Leo M. Frank. The letter was written by Judge Roan of Atlanta, Georgia, to Mrs. Wallace E.Brown, who was then Miss Jane Deity. The letter expressed the deponent's uncertainty of Frank's guilt due to the character of the Negro Conley's testimony. The letter also stated that the chief magistrate of the state should exert every effort in ascertaining the truth, and that the execution of any person whose guilt has not been satisfactorily proven to the constituted authorities is too horrible to contemplate. The deponent heard Judge Roan dictate the letter before copied and saw him read and sign the name.

Judge Roan had stated to Deponent that he was not convinced of Frank's guilt and that if executive clemency were asked for Frank, he intended to recommend commutation. The next morning, some 50 determined looking men from Cobb County marched into the Prison Commission office and demanded the hearing be reopened. They included former governor Joseph M. Brown and Herbert Clay, solicitor of the Blue Ridge Circuit. Clay spoke for hours against Commutation arguing that Georgia would be dishonored for all time if Frank were spared for his alleged abominable crime. The commission reopened the hearing and the commissioners listened intently and said nothing.

At the end of the reopening, they issued a statement that they would offer their recommendation to Governor Slayton in a week by a two to one vote. On June 1915, the commissioners refused to recommend commutation to Governor Slayton, leaving it up to the governor.